BAL Spotlights Series

Anna Schotthoefer, PhD, a project scientist at Marshfield Clinic Research Institute in Wisconsin, discusses the collection and analysis of a specific subset of blood and urine samples for Lyme Disease Biobank—a Bay Area Lyme Foundation program—from patients diagnosed with tick-borne diseases in the state. Marshfield Clinic serves a large population in Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which are highly endemic for Lyme disease. Her Bay Area Lyme-funded study of the Marshfield samples focused on visual documentation of rashes associated with Lyme disease and the challenges in accurately diagnosing the disease based on these rashes. The results highlight the difficulties in recognizing early Lyme: only two of 69 patients presented with the classic bullseye rash that doctors learn is the gold standard for diagnosing Lyme from textbooks. Schotthoefer discusses the variety of different rashes that can result from a tick bite, the characterization of the spectrum of rashes, the need for better Lyme diagnostics, and the ongoing efforts to develop new testing methods using the samples collected in LDB. She expresses optimism that in the next five to ten years, there will be significant advancements in Lyme disease detection, diagnosis, and therapeutics—largely thanks to patients who have contributed samples to LDB for ongoing research.

Anna Schotthoefer, PhD, a project scientist at Marshfield Clinic Research Institute in Wisconsin, discusses the collection and analysis of a specific subset of blood and urine samples for Lyme Disease Biobank—a Bay Area Lyme Foundation program—from patients diagnosed with tick-borne diseases in the state. Marshfield Clinic serves a large population in Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which are highly endemic for Lyme disease. Her Bay Area Lyme-funded study of the Marshfield samples focused on visual documentation of rashes associated with Lyme disease and the challenges in accurately diagnosing the disease based on these rashes. The results highlight the difficulties in recognizing early Lyme: only two of 69 patients presented with the classic bullseye rash that doctors learn is the gold standard for diagnosing Lyme from textbooks. Schotthoefer discusses the variety of different rashes that can result from a tick bite, the characterization of the spectrum of rashes, the need for better Lyme diagnostics, and the ongoing efforts to develop new testing methods using the samples collected in LDB. She expresses optimism that in the next five to ten years, there will be significant advancements in Lyme disease detection, diagnosis, and therapeutics—largely thanks to patients who have contributed samples to LDB for ongoing research.

“The textbooks doctors read in medical school tell them, ‘Look for a bullseye rash; look for the target-like lesion,’ and it turns out that’s wrong. There is a need to continue educating clinicians and providers that Lyme rashes are a spectrum.”

– Anna Schotthoefer, PhD

Diagnosing any infection or illness based on the physical appearance of a rash alone may sometimes be challenging even for experienced clinicians, but in the case of Lyme disease, if a doctor knows that a Lyme rash is not always a bullseye presentation, that can make the difference between a patient getting immediate antibiotic treatment to combat the infection during the acute phase or result in a significant delay allowing the infection to spread unchecked.

Misidentification of Rashes Hampers Early Treatment

While we wait for new tests that will provide accurate diagnostics for Lyme disease, doctors and patients face varied and complex challenges trying to determine whether or not the appearance of a rash somewhere on a patient’s body is a result of a tick bite or not. As many clinicians, researchers, patients, and their families will attest, the rash problem is only one of the more frustrating aspects of Lyme, further complicated by the fact that not everyone who gets Lyme develops a rash. Current laboratory testing is often inaccurate during the acute or early stages of the disease, resulting in false negatives that throw even more confusion into the diagnostic mix, therefore identification of the erythema migrans (EM) or Lyme rashes correctly can be critical to positive health outcomes. Research scientist Anna Schotthoefer embarked on an investigation to record the variety of rashes on patients infected with early Lyme disease to study this clinical challenge.

Schotthoefer has worked as a project scientist at Marshfield Clinic Research Institute since 2010 and for her research, she has had to learn as much about Lyme disease and its clinical presentations—or perhaps more—than the average family doctor. The size, number, and locations of the clinics within the Marshfield Clinic organization offer a unique ability to gather and investigate data on tick-borne diseases and how they present in patients. Marshfield serves about 3 million people in a geographic region highly endemic for Lyme disease. Every year, the clinics may see 500-1000 Lyme disease cases coming into their system, making it the perfect collection partner for Lyme Disease Biobank (LDB) studies to further our understanding of tick-borne diseases.

With a background in epidemiology, infectious disease, and the ecology of infectious diseases, Schotthoefer worked on Lyme disease as part of her PhD program in the 1990s. Awareness of Lyme disease in ticks was starting to emerge in the general media as reported in Newsweek Magazine in May 1989. She conducted fieldwork in Wisconsin, trapping mice and looking for the blacklegged or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) in parts of the state where it had yet to be reported. Lyme (Borrelia burgdorferi) was found and recorded, along with coinfections like anaplasmosis and babesiosis.

Schotthoefer is quick to point out that Lyme is a relatively recent invasion in some parts of Wisconsin. In terms of the documentation of infected ticks, she highlights the role of geography and topography vis-à-vis human exposure to tick bites and how things have changed over time. She explains, “Wisconsin has a lot of lakes, forests—places that people like to get outdoors and recreate, and simply live, and unfortunately, that’s also where the deer and the ticks are.” Back in the 1980s when ecologists started looking for deer ticks, they would typically only find them in the western part of the state. She adds, “Since then, the tick has migrated across the whole state and has been detected in every county in Wisconsin with pretty significant populations in some new areas of the state.”

Funding Research is the Key to Learning More About Lyme Disease

As Schotthoefer learned more about Lyme, infected ticks, and the impact of the disease on humans, she quickly realized the need for improved laboratory diagnostics for these diseases and saw that there was also a big knowledge gap. She notes, “Collectively, across clinicians and scientists, we simply do not know what every case of Lyme looks like. In particular, what physicians learn in medical school about identifying Lyme disease rashes, may not be complete.” Schotthoefer considered this incomplete knowledge of Lyme rashes an opportunity for further study. Lyme Disease Biobank already had an established relationship in place with Marshfield Clinic as an existing blood and urine collection site for Lyme patient samples because of the clinics’ locations in Lyme endemic areas, so Schotthoefer saw the opportunity for a concurrent research project to look specifically at Lyme disease rashes within the patient population at Marshfield.

Like most researchers, having access to money and resources is critical to launching investigations that add to our growing body of knowledge about infectious diseases. Fortunately, as LDB is a program of Bay Area Lyme Foundation (BAL) and BAL provides grants to researchers conducting investigations into Lyme and tick-borne diseases, Schotthoefer secured a grant from BAL to study rashes from Marshfield patients enrolled in the Biobank and describe their varied presentations. Wendy Adams, Bay Area Lyme Foundation’s Research Grant Director notes: “BAL was happy to support this study. People and providers must understand that not everyone infected with Lyme disease gets a rash. However, in this instance, the patients enrolled in the Biobank who did not have rashes were ineligible for this particular study because we were specifically focused on Lyme disease rashes.”

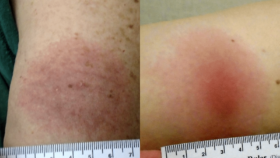

As part of their participation in the Biobank, patients’ rashes were measured and photographed. The comprehensive visual documentation of expanding Lyme rashes, known as erythema migrans (EM) rashes, was an important aspect of the LDB study. As Schotthoefer explains, “There are huge challenges in terms of being able to recognize erythema migrans and what Lyme rashes look like. With this study looking specifically at rashes, we could see the variation in the types of rashes participants in the Biobank collection presented with.” Furthermore, two clinicians—George Dempsey, MD, from East Hampton Family Medicine in East Hampton, NY, and Clayton Green, MD, PhD, from the University of Rochester, NY—looked at and rated each patient’s lesions based on their clinical experiences and what they thought the lesions represented.

Wendy Adams describes how misidentifying Lyme disease rashes is contributing to the growing problem of Lyme misdiagnosis in the US: “Healthcare providers often won’t rule in Lyme disease unless someone presents with a bullseye rash. The problem is that any presentation of rash—especially in an endemic area like Wisconsin—is sufficient, but not necessary, to rule in Lyme disease. Rashes will be different shapes and sizes, and until our medical education reflects this heterogeneity of disease presentation, healthcare providers will keep misdiagnosing Lyme at an alarming rate.”

Surprising Results on the Number of Bullseye Rashes Recorded

The results of the rashes study were striking. Schotthoefer notes, “So few patients presented with the classic bullseye rash. As Lyme disease researchers, we were aware of publications from Dr. John Aucott at Johns Hopkins University (and BAL Emeritus Scientific Advisory Board member), showing that EM rashes can come in different forms and that healthcare providers were often not able to identify atypical Lyme rashes. What’s interesting is that anecdotally, Marshfield Clinic physicians who have been around for a while will tell you it’s rarely a bullseye rash.” In fact, contrary to what doctors in medical school are taught to expect, Schotthoefer points out, “Lyme rashes are more typically larger red expanding plaque-like lesions. Although we knew that going in, I was still surprised at how few classic bullseye rashes we saw in our study. There were only two bullseyes out of 69 patients with EM rashes.”

“Lyme rashes are more typically larger red expanding plaque-like lesions. Although we knew that going in, I was still surprised at how few classic bullseye rashes we saw in our study. There were only two bullseyes out of 69 patients with EM rashes.”

– Anna Schotthoefer, PhD

Reflecting on these findings, Schotthoefer agrees that one of the biggest challenges in Lyme disease diagnostics (as we wait for the development of accurate diagnostic tests) is limited provider education and the need to deliver accurate messaging about rashes. At Marshfield, she noted that this is especially critical when new doctors and other healthcare providers come into the organization from outside the region or from a location that is not a Lyme disease endemic area. She defines the challenge succinctly: “The textbooks doctors read in medical school tell them, ‘Look for a bullseye rash; look for the target-like lesion,’ and it turns out that’s wrong. There is a need to continue educating clinicians and providers that Lyme rashes are a spectrum.”

Documenting Visuals of Rashes will Help Doctors and Patients Identify Lyme

Schotthoefer’s other interest in conducting the study and collecting pictures of rashes was to approach the lesions from the perspective of their characteristics, i.e., to observe and record characteristics of the lesions and see if they could use information on those other characteristics to help guide clinicians on lesions and determine the characteristics they should be looking for. She describes the types of questions on lesion characteristics she asked to be documented, tasking physicians to assess each rash and note:

“Is shape important? Is the size important? How well-defined are the margins of the lesion? Is there scaling involved? Is there blistering? We introduced these other morphological characteristics of lesions to help guide others. Could we identify some characteristics to share with clinicians in terms of an erythema migrans rash? One thing evident from our study is that the erythema migrans rash should have a well-defined margin. There shouldn’t be a lot of scattering of redness away from the edge of the margin of the rash. There should not be any scaling. There’s no raised edge to the rash. We were trying to characterize all of that and put it into some kind of context that might be helpful for others.”

“One thing evident from our study is that the erythema migrans rash should have a well-defined margin. There shouldn’t be a lot of scattering of redness away from the edge of the margin of the rash. There should not be any scaling. There’s no raised edge to the rash.”

– Anna Schotthoefer, PhD

The variability of EM rashes and the need to educate physicians regarding the spectrum of presentations only highlight the need for accurate diagnostics for early/acute Lyme disease. Schotthoefer’s 2022 paper on the confusing aspects of EM rashes underscores the diagnostic challenges inherent in Lyme disease. Bolstering our understanding of this diagnostic challenge are data from a wider LDB study of 550 Lyme patient samples gathered not only from the Marshfield Clinics but also from additional collection sites in East Hampton, NY, and Martha’s Vineyard, MA. This earlier study, which was conducted over five collection seasons with results published in 2020, highlighted the known limitations of serologic testing in Lyme disease. Schotthoefer extrapolates the key point: “In the larger sample collection that includes blood and urine taken not only here in Wisconsin, but also from patients on the East Coast, only 29% of individuals presenting with an EM lesion greater than five centimeters yielded a positive Lyme test using the ELISA and Western blot. This means that if you’ve got a hundred people walking into a doctor’s office with some kind of a lesion that looks like it could or couldn’t be Lyme, only 30% of them are going to potentially test positive on the standard testing that physicians have at their disposal right now due to the time lag that it takes for the immune system to mount a response to the Lyme bacteria. That’s a severe limitation for doctors unfamiliar with Lyme rashes who are trying to make a diagnosis.”

In the absence of an accurate diagnostic test, patients are left with the doctor’s opinion as to whether or not to treat for Lyme based on his/her knowledge and experience—a less than satisfactory situation. Yet, guidance for providers is clear: They are to treat if the EM rash is greater than 5cm in diameter in the absence of Lyme diagnostic testing. However, depending on personal experience, location, known prevalence of infected ticks, and the likelihood of seeing patients with Lyme rashes, not all clinicians will recognize that their patient is infected with Lyme. Doctors may elect to test and see if more evidence can be gathered. Schotthoefer knows this is less than ideal due to the limitations of current testing available and leads to patients falling through the cracks: “It ultimately comes down to each doctor asking him/herself, ‘Okay, am I going to treat this patient?’ However, those aren’t good options because you don’t want to wait to treat because the rash could disappear. And that early stage of infection is the most important time to start treatment so that you don’t end up with later stage manifestations or continuing symptoms that can occur if the disease isn’t recognized and treated early.”

Hope for the Future with Improved Lyme Diagnostics

Schotthoefer credits Lyme Disease Biobank with changing the landscape of Lyme disease research and awareness within the scientific community: “Lyme Disease Biobank came in and created a lot of awareness about the need for better Lyme diagnostics. Our Biobank has worked with scientists and lots of different companies and helped advance the work that’s going on with Lyme disease. It spurred interest in tick-borne disease within the CDC, NIH, and the federal government. The Biobank has pushed all of that along. We now have a receptive audience interested in solving the diagnostic problem. I believe that in five or 10 years, we will have a much better-defined case definition for Lyme disease. And we’ll have better laboratory diagnostics. I am sure of it.”

Schotthoefer credits Lyme Disease Biobank with changing the landscape of Lyme disease research and awareness within the scientific community: “Lyme Disease Biobank came in and created a lot of awareness about the need for better Lyme diagnostics. Our Biobank has worked with scientists and lots of different companies and helped advance the work that’s going on with Lyme disease. It spurred interest in tick-borne disease within the CDC, NIH, and the federal government. The Biobank has pushed all of that along. We now have a receptive audience interested in solving the diagnostic problem. I believe that in five or 10 years, we will have a much better-defined case definition for Lyme disease. And we’ll have better laboratory diagnostics. I am sure of it.”

“Lyme Disease Biobank has created a lot of awareness about the need for better Lyme diagnostics. It has helped advance the work that’s going on with Lyme disease. It spurred interest in tick-borne disease within the CDC, NIH, and the federal government. We now have a receptive audience interested in solving the diagnostic problem. I believe that in five or 10 years, we will have a much better-defined case definition for Lyme disease. And we’ll have better laboratory diagnostics. I am sure of it.”

– Anna Schotthoefer, PhD

Looking forward, Schotthoefer’s optimism is reassuring. As someone who has been down in the trenches in the world of Lyme disease for almost 15 years, she has her focus on the science but never forgets that her work, the Lyme rashes study, and her communications with doctors inside the Marshfield Clinics educating them about recognizing the different presentations of the rashes, and the publication of her papers are all designed to help improve patient outcomes. And new reservoirs of potential data on Lyme patients will be playing a part in her work going forward. “Right now, I’m busy with national repository studies collecting samples for researchers—again, it goes back to improving diagnostics for early Lyme disease. We’re starting to look into using the Electronic Health Record (EHR) to help better define Lyme disease, and we’re working with the CDC on a study to use the EHR as another source of data for Lyme disease surveillance. So, we always have our eyes on the horizon when it comes to gathering information about Lyme.”

Ultimately, the takeaway from Schotthoefer’s investigation of the 69 Lyme patients’ rashes is that everyone—not just doctors—needs to know that the bullseye rash has been proven to be an uncommon presentation for Lyme disease. If people only look for the classic “target-like” rash after a bite, an infection will be missed that could have significantly negative health consequences. At Bay Area Lyme, we are working to change this during Lyme Disease Awareness month so patients and clinicians are better prepared to recognize the characteristics of a Lyme rash, identify its features early, and treat it with an appropriate course of antibiotics.

“The best shot we have of curing someone with Lyme is diagnosing them early and treating them appropriately. Misdiagnosing the rash in Lyme patients can mean a person is given the wrong antibiotics or none at all, or treated with steroids, both of which make someone more likely to progress to and suffer from persistent Lyme disease. Studies like this one can help providers better understand different presentations of Lyme rashes. That the rash has multiple presentations has been known for decades, yet this is not reflected in medical school education. It’s time for the medical establishment to accept responsibility for medical education gaps that are causing patients to suffer needlessly. ” – Wendy Adams, Research Grant Director, Bay Area Lyme Foundation.

Anna Schotthoefer, PhD, is a Project Scientist at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, the non-profit research division of the Marshfield Clinic Health System in Wisconsin. She has a diverse background in epidemiology and infectious disease research. Over the past 12 years, her research interests have focused on efforts to improve laboratory diagnostics for tick-borne diseases and on utilizing electronic health record data for retrospective, population-based studies to better define the clinical presentation of tick-borne diseases, the practices providers use to diagnose and treat patients and to understand the factors that contribute to the need for extended care or treatment of the diseases, including Lyme disease.

This blog is part of our BAL Spotlights Series. Bay Area Lyme Foundation provides reliable, fact-based information so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. If you require a copy of this article in a bigger typeface and/or double-spaced layout, please contact us here. For more information about Bay Area Lyme, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.

Please send me copy or tell where published

Hi John,

This blog is part of our “BAL Spotlight Series”. The article highlights work being done by Anna Schotthoefer, PhD at Marshfield Clinic Research Institute related to rashes and using the Lyme Disease Biobank samples. This research is ongoing and the blog is for awareness. This is not a new research publication. The links throughout the article reference the existing publications.

All the best,

Bay Area Lyme Foundation