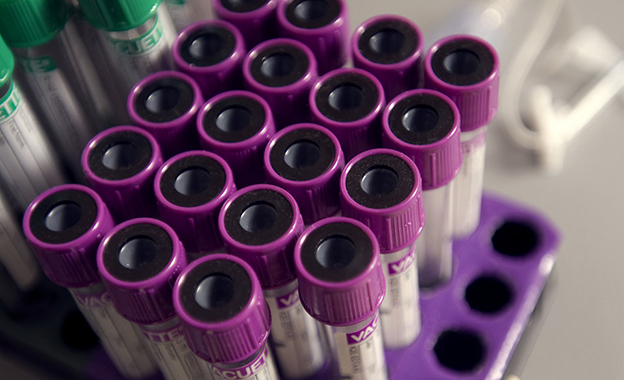

The national Lyme Disease Biobank (LDB) launched in Summer 2014 after a successful Fund-A-Need campaign at our annual LymeAid benefit. This initiative, which began with a pilot study in East Hampton, NY, a highly concentrated endemic area for Lyme disease, was designed to help address the shortage of clinical samples to support research into better diagnostics and treatments for Lyme disease. The goal is to create a geographically diverse and robust pool of biological samples (particularly blood, but also tissue and other fluids) characterized with sufficient clinical data and validation information about any co-infections that can then be drawn upon by researchers around the country, allowing for more projects to come to fruition. The biobank has already expanded significantly and released the first samples to researchers last year, supporting a new wave of projects.

The national Lyme Disease Biobank (LDB) launched in Summer 2014 after a successful Fund-A-Need campaign at our annual LymeAid benefit. This initiative, which began with a pilot study in East Hampton, NY, a highly concentrated endemic area for Lyme disease, was designed to help address the shortage of clinical samples to support research into better diagnostics and treatments for Lyme disease. The goal is to create a geographically diverse and robust pool of biological samples (particularly blood, but also tissue and other fluids) characterized with sufficient clinical data and validation information about any co-infections that can then be drawn upon by researchers around the country, allowing for more projects to come to fruition. The biobank has already expanded significantly and released the first samples to researchers last year, supporting a new wave of projects.

Liz Horn, PhD, MBI, a noted expert experienced in building complex biorepositories and other bio-based technological solutions working with a wide array of researchers, institutions, and other agencies, was brought on as the Principal Investigator for the LDB. Dr. Horn has deep expertise in basic science, cancer biology, bioinformatics, registry questionnaire design, and biobank planning and operations.

Liz Horn, PhD, MBI, a noted expert experienced in building complex biorepositories and other bio-based technological solutions working with a wide array of researchers, institutions, and other agencies, was brought on as the Principal Investigator for the LDB. Dr. Horn has deep expertise in basic science, cancer biology, bioinformatics, registry questionnaire design, and biobank planning and operations.

We talked with Dr. Horn about the progress they have been making at the Lyme Disease Biobank.

Tell us about the Lyme Disease Biobank (LDB). Why is a biobank an important undertaking, particularly for the field of Lyme research?

“The Lyme Disease Biobank is a collection of human biological samples that catalyzes and facilitates research in Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections. We are collecting blood samples from people with suspected acute Lyme disease presenting with or without an erythema migrans (EM) or annular rash (cases) and also unaffected individuals (Lyme disease negative controls).

“Researchers lack the samples they need for their work in Lyme disease. Especially for early, acute cases, patients typically present at the emergency room, urgent care, or to a family physician. These patients typically are not presenting at academic medical centers – the places where there is a lot of research happening. It’s more challenging to collect samples in these research facilities. Plus, most researchers are focused on doing the research, not setting up collaborations to collect samples, which can be time-consuming, complicated, and laborious.

“Notably, by compiling samples nationally — and with sufficient characterizing data — sample groups can be better designed to meet the specific research needs. Where it might take years to amass sufficient samples with the right attributes at one research facility, it is a lot more efficient to draw across a wider pool. And, patients who participate in biobanks also typically consent to share health information and / or samples over time, allowing for more robust and longitudinal analysis. By reducing the bottleneck for research samples, more researchers can work on their experiment opening up avenues for new diagnostics and treatments.”

What sort of research do you see this resource now making possible?

“We have samples that people can use to test new diagnostics, including serology assays and next-generation sequencing. Investigators could also identify biomarkers for Lyme disease with our samples. It is impossible to know what all can come from this work but it is exciting to see the level of interest and participation, clearly pointing to the need and opportunity for new research investigations.”

How did you come into this field of work?

“I came into the field of biobanking by chance. When I was working on my dissertation, I needed samples from head- and neck-cancer patients — both cancerous tissue and uninvolved tissue surrounding the cancer site. To obtain the tissue, I set up a program in our lab to collect tissue from the operating room(OR), and this evolved into a Molecular Profiling Resource, which is still active, collecting and distributing tissue.

“For Lyme disease, I was introduced to Bay Area Lyme by a colleague, and I instantly knew the field of Lyme disease could benefit from a central biorepository. Three years later, we are collecting at multiple sites across the country and have distributed our first set of samples to researchers who are already working with them in labs!”

How does a biobank work? How long can the samples be maintained?

“The LDB is a prospective research study. That means that people consent to donate a sample and that sample is stored in a central lab. We also collect detailed clinical information on the person donating the sample. These samples are then released to researchers through an application process. Samples can be stored for a long time – they are stored at -80 degrees Fahrenheit at our biorepository facility. By storing them very cold, it prevents any loss of activity. Samples can be stored and accessed for years.”

How much is collected from any one patient? And how many patients do you need in the database to be able to support new research?

“We are collecting approximately 4T of blood from a patient. We already have samples from ~300 people. We have released samples from the first 120 participants and are just beginning to release samples from last year’s collection. (There is typically a 8-10 month processing cycle. East coast collection is during the late Spring to Summer and all samples involve a secondary collection six months post to assess changes in the bacteria count. Adding the West Coast site will lengthen our collection timeframe.) We are hoping to have more than 500 participants in the biobank over the next several years. The really cool thing is that each donation from a participant can support up to 50 research projects!”

Will the biobank also support the study of other tick-borne diseases or just Lyme?

“Yes – our main focus is Lyme, however the samples may be useful to people studying other tick-borne illnesses. We know that it is common for Lyme patients to have co-infections. That is why we test for other things like Babesia and Anaplasma.”

This endeavor is the result of a LOT of collaboration among scientists from all over the country and many esteemed research institutions – a complicated undertaking in the best of circumstances. Tell us a little about the process and the progress made to date?

“We have great partners – and we couldn’t do it without them. We have collected at sites on Long Island, Martha’s Vineyard, in Wisconsin, and in California. We have collaborations with people testing our samples for co-infections and for Lyme serology. We also have a group of almost forty scientists who volunteer their time to review applications for samples. This biobank is a precious resource and we want to make sure the samples are used for the best science and not wasted.

“We also couldn’t do any of it without the people participating in the study. They come to see the doctor because they aren’t feeling well, and they generously give us a blood sample to move research forward. We are so grateful for their participation and blood donations. It’s all these people working together that will help us get to better tests for Lyme disease.”

What has been most challenging about getting the biobank up and running?

“The seasonality of collection. For our East Coast sites, we collect during the summer – so the collection window is quite short. And then you have to wait until next year.

“In some parts of the country, like California, the tick and Lyme season is much longer due to the milder climate. As we add on more collection locations we will be able to extend our sampling season.”

How would you describe the progress to date? Has the collection been able to support new research already or are you still in the developmental phase?

“We are thrilled to be collecting in multiple regions of the country. We have investigators applying for and working with samples. It is exciting to have made this much progress already.

“One of the unique aspects about this project is that we require the investigators who use our samples to provide us information on their test results. We want to know how many times a sample tested positive for Lyme disease – and that is where the real value is. Knowing that sample A tested positive in eight of ten tests, and sample B tested positive in three of ten tests is incredibly valuable. It’s constantly increasing and improving the knowledge base.”

What do you envision for the biobank in, say, five years?

“We will have samples from many people with Lyme disease, including people just diagnosed and those who have struggled with it for a long time. We will also collect other sample types, like tissue. This will be a robust resource, and may investigators will be using our samples and developing new methods and approaches for diagnostics and therapeutics. It is very exciting!”