Ticktective Podcast Transcript

In this interview, psychiatrist Dr. Robert Bransfield explains the links between neuropsychiatric disorders and infections. He recounts his successes treating patients who repeatedly fail to respond to conventional interventions. Dr. Bransfield describes how clinical diagnoses of infection, along with correct administration and interpretation of testing, plus treating patients with antibiotics can, in many cases, lead to an abatement of a variety of psychiatric disorders, from psychosis to depression and anxiety. He also explores the connection between tick-borne diseases in maternal-fetal transfer of infections and the rise in autism in children.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity. Bibliography and references are posted below.

“What are people in the future going to say about the Lyme crisis? I’m sure this will be judged by history as a great failure of our healthcare system, that we didn’t move quickly enough with this, and that people were holding back progress.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

Dana Parish: Hi, I am Dana Parish, and I am hosting the Ticktective podcast on behalf of Bay Area Lyme Foundation. I am here today with a wonderful psychiatrist, Dr. Robert C. Bransfield, MD, DLF APA. He is a graduate of Rutgers College and George Washington University School of Medicine. He completed his psychiatric residency training at Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital. He’s board certified by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology in psychiatry and is a distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. He’s a clinical associate professor of Psychiatry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, and he is well published in the peer reviewed literature. Welcome Dr. Bransfield. Thank you so much for talking to me today. How are you?

Robert Bransfield: Thank you for inviting me.

Dana Parish: It’s my pleasure. I’ve learned so much from you over the years about microbes and mental illness. You’ve blown my mind a million times and I cannot wait to share your knowledge today with everybody who’s going to watch and listen to this podcast. So, my first question is, does psychiatry pay enough attention and does medicine pay enough attention to microbes in infections and pathogens in mental illness? And if not, what is going on with the brain when we get neurologic infections?

Robert Bransfield: Well, not enough. If you look at the old views of what caused psychiatric issues, it was thought to be demonic possession. Then we blamed our mothers, and then we blamed serotonin. It doesn’t quite make sense (to people) that there’s something that causes psychiatric illness. But these illnesses don’t just come out of nowhere.

Robert Bransfield: Well, not enough. If you look at the old views of what caused psychiatric issues, it was thought to be demonic possession. Then we blamed our mothers, and then we blamed serotonin. It doesn’t quite make sense (to people) that there’s something that causes psychiatric illness. But these illnesses don’t just come out of nowhere.

The problem is that nothing in the known universe for its size is more complex than the human brain. So, understanding the pathophysiology of the human brain is very challenging, especially the part involving psychiatric illness. That is much more complicated than general neurological illness where the circuits are not as complex as the circuits that impact psychiatric functioning. So, this causes a problem. When we look at all the possibilities, there are many things that contribute to mental illness—microbes are just one of them. But I think they are a very significant one and when you look long and hard enough, this does explain many psychiatric illnesses.

However, it’s not just the microbes. People have to have a genetic vulnerability. There aren’t really mental illness genes, but there are certainly genes that are triggered by environmental circumstances, and infections are one of the many significant contributors to this. Now that we have better brain imaging technology, neurochemistry, gene expression, upregulation, and downregulation awareness, the more we look at that, the more we’re seeing that infections do play a role in psychiatric illness, but they’re mediated by an immune process. There’s infection and there’s an immune process, and these things cause circuit changes and mental illnesses.

However, a lot of people that were trained in medical school decades ago were taught that the brain is a mysterious black box and psychiatric illness just comes out of nowhere and there’s no explanation for it. And now we know there is. It’s certainly complicated, but it can be explained.

“People that were trained in medical school decades ago were taught that the brain is a mysterious black box and psychiatric illness just comes out of nowhere and there’s no explanation. It’s certainly complicated, but it can be explained.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

Dana Parish: Are some of these microbes actually in the brain along with the different immune factors that are going on?

Robert Bransfield: I think there are three basic things: 1) There may be infection in the brain itself, and 2) there can be infection in the body. In the body, an infection has an immune effect and a metabolic effect, which in turn impact the functioning of the brain. So, immune activity in the body has an immune effect in the brain, and that alters brain functioning. 3) This is when there is infection in the vasculature that affects circulation, which in turn impacts mental psychiatric and neurological functioning.

So, those are the three mechanisms. People need to better understand infection in the brain. A lot of the time, they make the mistake of thinking that you have to have signs of infection in the brain in order for an infection to impact brain functioning. More often it seems that infection in the body can do it. The other thing that further complicates the situation is that there may be a prior infection that’s had an impact—a dysfunction that then persists long after the infection is gone.

Dana Parish: I see. So, is there a way to find out whether your neuropsychiatric symptoms, your psychiatric symptoms, are caused by an active infection versus something else?

Robert Bransfield: You need to look at all the contributors to disease and all the deterrence to disease and you have to add them up. One thing to consider is, what triggers it in the first place? What causes it to perpetuate? What causes it to progress? So, a very significant thing is doing a thorough history of the patient—a very thorough assessment—looking at how the history evolved and looking at all the symptoms. When you have these infections, they are invariably multisystem, i.e. they infect and impact the entire body. You can’t use what we call a “silo mentality” where you just look at a narrow area. An example of this would be schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Those people don’t just have a mental illness. They invariably have a cardiovascular component and a metabolic component to their illness. So, they have something else that affects them.

As psychiatrists, we pay more attention to the psych part. For instance, schizophrenic patients may die 19 years sooner than the average person, and bipolar patients 13 years sooner—not necessarily from suicide—but often from these general medical problems. So, you have something causing that immune reaction, causing dysfunction, that is multisystem, and a lot of these things are falling into that category. So, you have to do an old-fashioned medical student workup that, unfortunately, with our algorithm-driven, computerized way of charting, is hard. It’s becoming a lost art to do an adequate patient history in an adequate multisystem review of systems exam in a way that really reveals truly what’s going on.

“You have to do an old-fashioned medical student workup that, unfortunately, is becoming a lost art. You need to do an adequate patient history in an adequate multisystem review of systems exam in a way that really reveals truly what’s going on.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

Dana Parish: Yes. I don’t hear about any psychiatrists even evaluating for infections or considering infections. And that’s one of the reasons why I really wanted to talk to you today because I think that the amount of education that you’ve given to doctors and how you have changed their minds about this has been reverberating throughout their patient practices. I hear from people that did get the diagnosis right, but I heard more from those whose doctors missed it and those patients suffered for a really, really long time. I’m wondering, what are the most common infections causing psychiatric manifestations, and what are the most common manifestations of these diseases?

Robert Bransfield: It is in the American Psychiatric Association guidelines for the assessment of adults to consider Lyme disease. That is there.

Dana Parish: That’s great to know, but why don’t they do it?

Robert Bransfield: I think some do it. We do symposiums to teach people about it. And I think gradually once you start seeing it, then you can’t stop saying it. It’s like the Yogi Bear quote, “I never would’ve believed it if I didn’t see it.” And once you see it, then you think, “Oh my god, I’ve been missing this all the time.” Remember, psychiatrists are trained in general medicine first and then in psychiatry. So, we’re physicians first and specialists second.

Let’s go back in time and talk about syphilis. Syphilis was clearly a good example of an infection causing psychiatric illness. Many state hospitals were filled with syphilis patients. Then once that was treated with penicillin, doctors kind of drifted away from seeing it (as a causative agent).

But there has been awareness of many different infections. The infections are usually the three “V”s. The three “V”s are: vector-borne, venereal, and viral. And invariably you’re looking at these low-grade infections that can linger. Now, some are what I would call “hit-and-run” infections that may do their damage and leave. Some may be chronic, but they may be hard to detect. And some may be relapsing and remitting.

Think of shingles as an example. When you’re immunocompromised it may be reactivated. So, infections may fall into these categories, but I think we have to pay a lot more attention. We know how to treat symptoms in psychiatry, and we have drugs that we have never had before that treat symptoms—and that’s wonderful. But treating symptoms is only part of it. We have to look at what caused it in the first place. And is what’s causing it still contributory? So, we may have to address infection, and we may also have to address the immune reaction because the symptoms are invariably immune mediated and metabolic mediated. There’s a vicious cycle of how these three components interact, but also, we need to educate (doctors) so that there’s an awareness of how these components interact so we can break that cycle in more than one way. That gives us more options for treatment and more options for prevention.

Dana Parish: I completely understand. There are so many layers to this and it’s so hard to unravel sometimes when you’re the patient. Where do I go first? What should I do? Will my doctors work together? These are just such complex diseases.

Robert Bransfield: In one of the journal articles I wrote, I took a hundred patients that were clearly CDC positive for Lyme so that no one could say, “Well, that wasn’t Lyme.” Then I did my complete assessment, which is about 277 questions. And the average patient with Lyme had 82 of those symptoms. Now, the average medical student that was one of the controls (I had four controls), had four symptoms. The average patient who was a Lyme patient in looking at their history retrospectively had four symptoms originally (before they got Lyme). So, they went from having four to 82 symptoms. When you have that many symptoms, how do those symptoms interact and contribute to disease progression? As a doctor, when you are figuring out a treatment plan, you look at that number and “Where do I start?” Are you going to give the patient 82 drugs? No. You have to look at what’s driving the illness—be it infection, or symptom, or immune functioning—and intervene in a way that’s most effective. And then you work your way down the list.

Dana Parish: What are the most common psychiatric manifestations of Lyme or other vector-borne diseases that you see?

Robert Bransfield: First let’s break it down into different areas: cognitive, emotional, behavioral, neurological, and general medical.

Cognitive can be broken down into four areas: attention, memory, processing and executive function.

- Attention can look somewhat like an acquired attention deficit disorder, but one difference is there is more sensory flooding/sensory overload. That’s what makes it different from attention deficit disorder. Often, in patients with Lyme, I’ll use the example of Times Square, in New York City, it’s just too much, I can’t take it. And it’s not just distractibility, it’s an inability to filter it out so it’s flooding and then that can make them aggravated. So, often that contributes to reclusiveness, but they also have low frustration tolerance or distracted a lot of the symptoms that we classically think of with ADD.

- Memory is impaired. Working memory and short-term memory are, in particular, compromised first. Long-term memory is usually preserved better, although often long-term memory is better before the onset of the disease. And it’s hard to develop new information and retain it. It depends on the severity of the disease.

- Processing is digesting what comes in and organizing what goes out. Slow and impaired mental processing is common. An example of this might be like the Peanuts cartoon where adults are talking and the children in the cartoon hear “Wah, wah, wah.” You hear people talking but you’re not digesting it fast enough to be part of the conversation and be able to give an answer. There’s this slowness. It’s like the old computers that were slow to download websites. And for expressive, you can see where someone struggles, where there may be errors in processing, saying the wrong word, it’s called neologisms.

- Executive functioning is the ability to create goal-directed behavior. People can experience a lot of problems with time management. Patients have difficulties in organizing, planning, and prioritizing that they never had before. Although innate intelligence can remain intact, organizational skills are compromised.

So those are the cognitive issues. Then in addition to those areas are the psychiatric illnesses listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) like depression, different kinds of anxiety, and mood swings—particularly when someone younger is infected. I think the age at which you’re infected definitely has a bearing on how the disease manifests.

Dana Parish: Interesting.

Robert Bransfield: Then we need to talk about behavioral symptoms. One particularly notable thing is the intrusive thoughts. We often associate intrusive thoughts with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) where there is a thought or an image that’s not something you would voluntarily want to think and it just comes into your head and it is frightening.

These can be horrific images in your mind, or urges to do things that are inappropriate, destructive, or aggressive. And people go “Where did that come from?” It often occurs with temporal lobe activation. There is evidence of suicidality—sometimes homicidality—although that’s not common, but a large number of people may be impacted. A Chinese study showed that 14.5% of the population has been exposed to Lyme disease. So, this is pervasive and it’s throughout the world. We should be considering it constantly in psychiatry and in general medicine. It’s definitely a contributor—but maybe not the sole contributor—to illness.

Dana Parish: Absolutely. Now, we have the pandemic of Covid-19, and we know that that impacts the brain, and it is also a neurologic infection and it goes all over the body. What are you witnessing? Is there an overlap between Lyme and vector-borne diseases and acquiring Covid-19? Are the symptoms the same? What does it look like?

Robert Bransfield: When there’s a new emerging disease, there is often great difficulty handling it effectively. And there are some people that say, “Well, you have to give me research money so that I can do a controlled study and we can’t do anything until that happens.” What you really have to look at—and where there’s a failure—is looking at frontline physicians who deal with this. Because when you’re dealing with a patient and they’re in distress, you have to decide, “What am I going to do to help this person today?” As a doctor, I can’t wait until these studies are completed. We can always study more, and more, but there’s a limit. You can actually overstudy. Then it becomes an ethical issue i.e., when you overstudy something and you have a fair amount of knowledge already. So, you have the power play of, “Who is in control of this new emerging disease?” And there may be people who see it as an economic opportunity—for example getting approvals for different test kits. And then there are other frontline people that say, “Well, let’s work with what we have and make the best of it.” That doesn’t necessarily have economic potential for large entities, but it does help patients. So, there’s often that battle. We saw it with AIDS. We saw it with chronic fatigue. We saw it with Lyme. We saw it with Covid.

Then if you recognize that some treatments really work, it’s hard to get fast-track approval of other drugs that have economic potential. So, there’s often this battle and the finances and special interests interfere with what might be best for patients.

Dana Parish: I don’t think it’s a surprise that we’re seeing the same playbook that we have experienced with chronic Lyme. With chronic Covid, there was an article that came out recently in the New Republic called Head Case: We might have Long Covid All Wrong by Natalie Shure. This article claims that a lot of the psychiatric manifestations and manifestations of Long Covid, chronic Covid—whatever you want to call it—are functional neurologic disorders. They call it FND. What does that mean and is that a legitimate diagnosis?

Robert Bransfield: Well, that’s a cop out and it’s not legitimate, but it is what people do. And when you think of it, you have to look at the mind-body connection. There is psychosomatic illness, neuropsychic illness, and multisystem illness that affects both the mind and the body, and this is medical uncertainty. You have to label those four things appropriately. A lot of the time, where there’s medical uncertainty, there is a tendency to say what’s functional or psychosomatic.

Robert Bransfield: Well, that’s a cop out and it’s not legitimate, but it is what people do. And when you think of it, you have to look at the mind-body connection. There is psychosomatic illness, neuropsychic illness, and multisystem illness that affects both the mind and the body, and this is medical uncertainty. You have to label those four things appropriately. A lot of the time, where there’s medical uncertainty, there is a tendency to say what’s functional or psychosomatic.

You have to understand exactly what psychosomatic medicine is. Psychosomatic illnesses don’t suddenly begin in midlife. That doesn’t happen. These are typically lifelong tendencies. For instance, someone may have a vulnerability where stress goes to their stomach, or their bowels, or they sweat, or they have palpitations—that is there from childhood, and it doesn’t suddenly begin in mid-life after an infection. It’s always there. For some reason they may have a vulnerable organ and it may come and go with times of stress. So, when that person has stress, it becomes symptomatic, but there is really no such thing as multisystem psychosomatic illness that would suddenly be acquired abruptly. That doesn’t occur, it just doesn’t fit with the diagnosis. A lot of times it’s the cop out if you don’t know the diagnosis, but you’re trying to dismiss it.

A lot of the time, people want rigidity of diagnosis because rigidity of diagnosis makes it easier to use criteria for getting drugs, vaccines, or test kits approved. They often make it more rigid than it actually is so that you can have that economic potential fulfilled. So, a lot of people (doctors) really don’t know what they are dealing with. Is that doctor trained in psychosomatic medicine? Is that doctor a psychiatrist who’s also an internist who has that capability? Or is that someone who’s…? I don’t know what their background is, but I doubt they have the skillset to really look at that.

Dana Parish: It seemed like this was an agenda-driven piece. It was what I would call a hit piece. We’ve seen it a million times in chronic Lyme and that was the perception of the Long Covid community as well. And we now have approximately 300 studies that demonstrate persistence of the Covid-19 virus. So, to call it functional, I think people don’t understand how harmful that is to patients.

Robert Bransfield: Well, it’s probably beneficial to the health insurance industry to say this is functional and it’s not a disability. There’s a brain imaging article that shows there are physiological changes (after Covid-19) and if you measure properly, you can see that there are changes after the infection that weren’t there before. So, there is defined physiology when you look hard enough and when you do an adequate history and assessment. If you do a sloppy or biased assessment, then you can come up with those things. I’ve had different reporters contact me and I can sometimes tell that they have an agenda, and they want to promote something, because when I say something negative, it never gets included. Or they might include nothing that I say, or they may twist my words. And why are they doing that article? Who’s paying them? When you dig enough, there is often someone paying that person to write the article and they’re trying to promote some agenda and that’s not always clear. And it’s not always disclosed when that article hits the media.

Dana Parish: Absolutely true. So, in terms of the psychiatric manifestations of microbes, one of the things that you’ve talked about before is autism. I’m curious about the relationship between pathogens and autism and how you discovered that that was possibly happening.

Robert Bransfield: I specialize in treating treatment-resistant psychiatric illnesses. So, these would be patients that have failed on everything (every drug or treatment protocol) and then referred to me to try to figure out what else could be done. Some of these patients had an infectious component to their case—not all of them—but some. Once that had been addressed, then treatment was more successful. Years ago, I was getting a lot of AIDS patients, then chronic fatigue patients, then Lyme patients and psychiatric patients. When an illness is mismanaged in general medicine, patients are invariably referred to psychiatrists. Doctors say, “I can’t figure it out. It must be all in your head.” I would see these patients and see a lot of Lyme patients repeatedly, and some of my female patients would say in passing, “Oh, I happen to have an autistic child.”

“When an illness is mismanaged in general medicine, patients are invariably referred to psychiatrists. Doctors say: ‘I can’t figure it out. It must be all in your head.’ I would see these patients and see Lyme patients repeatedly.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

And I thought, “Gee, that’s interesting. You’ve got double trouble here. You’ve got Lyme and you have an autistic child.” And then another one would say it, and another one would say it, and another one would say it, and I thought, “Wait a minute. This is too much of a coincidence.” So, I looked into it further. I’ve written about eight different articles on Lyme and autism and the association between the two things, and as I looked at it further, I discovered that there are 22 different infections associated with autism. There are probably other causes that are contributors to autism, but there are certainly some infections that are well-recognized.

And I thought, “Gee, that’s interesting. You’ve got double trouble here. You’ve got Lyme and you have an autistic child.” And then another one would say it, and another one would say it, and another one would say it, and I thought, “Wait a minute. This is too much of a coincidence.” So, I looked into it further. I’ve written about eight different articles on Lyme and autism and the association between the two things, and as I looked at it further, I discovered that there are 22 different infections associated with autism. There are probably other causes that are contributors to autism, but there are certainly some infections that are well-recognized.

Dana Parish: These are passed on between mother and child in utero. We should probably say this because people don’t realize that microbes can be congenital.

Robert Bransfield: Correct. There can be two types of autism: You can have it passed on congenitally, but you can also have regressive autism. That’s where a child is not born autistic. They’re developing normally and then at a certain point—typically when they are between one-two years-old—they suddenly “crash.” Their development declines and they show autistic symptoms. And those patients are usually the easier ones to treat.

Dana Parish: What’s the difference in terms? You’re saying those are not congenitally infected kids?

Robert Bransfield: Right.

Dana Parish: They acquired it out in the world?

Robert Bransfield: They acquired it early and it’s difficult to test for because the immune system may not see it as being foreign. You really have to know that the testing for this is not reliable. That’s the problem.

I wrote one article where I looked at three generations of Lyme with autism, and now there’s a fourth (generation) in that family. The grandmother had Lyme in her heart at autopsy; she had Lyme and other tick-borne infections. Then the mother had autistic traits. The mother had four children with autism. And then one of those children then went on to have two autistic children, and we have the brain imaging showing the deficits. We had the blood work. So, yes, it comes up a lot. When you recognize it and you treat it in some of these patients, you see surprising improvement in the autism. Now, when you consider that a case of autism can cost societies several million dollars in a lifetime of management—if you can treat that and prevent it, that’s a wonderful thing to do. Not just because of the cost, but because of the emotional distress and the impact on the family and the patient. So, I think that’s significant. We have to look at some of these things that are baffling. Why is there more and more autism than there used to be?

Dana Parish: I was just going to ask you about that.

Robert Bransfield: It is increasing. Let’s look at these infections. It can be a mixed infection, and when you have mixed infections there’s an interactive effect. Think of AIDS as an “interactive infection.” In the example of AIDS, 1+1 doesn’t equal 2. Rather, 1+1 equals 11. However, it’s not just 1+1. There may be multiple things. There may be multiple infections that we haven’t yet identified. Every year we are finding new tick-borne diseases, or new strains, and it’s a lot more complicated. We have to have the humility and not the arrogance that has been prevalent with regards to tick-borne diseases. We have to be open to understanding these infections, but it takes a multidisciplinary approach with people who don’t usually work together and (it’s like they) speak different languages.

“Every year we are finding new tick-borne diseases, or new strains, and it’s a lot more complicated. We have to have the humility and not the arrogance that has been prevalent with regards to tick-borne diseases. We have to be open to understanding these infections, but it takes a multidisciplinary approach with people who don’t usually work together.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

Dana Parish: Absolutely. When you’re treating a patient at the same time as (another medical professional) who might also be treating your patient for an underlying vector-borne disease or chronic Covid kind of issues, if you’re treating (that patient) with psych medications… As that person’s health improves under treatment for the underlying cause, are they sometimes able to get off of psychiatric meds? And how common is that?

Robert Bransfield: Yes. I have seen that sometimes. Not always. It depends on how entrenched the illness is. If it’s been there for a long time, you can see disease progression but sometimes you can’t always reverse it by treating the infection that started everything in the first place. You can’t always stop an avalanche at the bottom of the hill, but sometimes you can. And a lot of times when you treat someone with psych meds, that patient is less stressed. And if they’re less stressed—and particularly if you treat sleep disorders—those two things help their immunocompetence to improve, and then they’re better able to ward off whatever infections might be there that are still causing disease progression. Sometimes the infection causing disease progression may be different than what originally started it.

Dana Parish: Interesting. One of the things that we quoted you on in our book, Chronic, written by Dr. Phillips and me, was about sleep. And you really talked a lot about how important sleep is. People peripherally know that, but not as deeply as you do. One of the things that I thought was so interesting is that you said pretty much all of your Lyme patients have some kind of sleep disturbance. What’s that about? What kind of disturbances? Is it all insomnia? Is it trouble waking up? Are people just chronically fatigued? What’s the problem?

Dana Parish: Interesting. One of the things that we quoted you on in our book, Chronic, written by Dr. Phillips and me, was about sleep. And you really talked a lot about how important sleep is. People peripherally know that, but not as deeply as you do. One of the things that I thought was so interesting is that you said pretty much all of your Lyme patients have some kind of sleep disturbance. What’s that about? What kind of disturbances? Is it all insomnia? Is it trouble waking up? Are people just chronically fatigued? What’s the problem?

Robert Bransfield: A lot of it is what is referred to as “non-restorative” sleep. There was a prior study by Greenberg that showed a hundred percent of Lyme patients had sleep disorders at one time or another. So, non-restorative sleep is a big thing because if you’re not getting Delta sleep that’s a big problem. Delta sleep is where your body regenerates and it helps with immuno-confidence, with early inflammation, later adaptive immunity, and then that contributes to growth hormone. That’s a master hormone.

So, you get hormonal disruption and then you get the terrible triad and non-restorative sleep fatigue, cognitive impairments, brain fog, et cetera. That’s frequently where I intervene first. Then I have to say, “Well, what is the sleep disorder?” So, if it’s non-restorative sleep, then I think about what would promote deep sleep or Delta sleep. And does the patient have trouble falling asleep? Trouble staying asleep? Early morning awakening?

There are different explanations for trouble falling asleep. Are there thoughts? Is it emotion? Is it physical discomfort, a physical symptom? Then there’s waking up in the middle of the night. A lot of times the various physical things that disrupt sleep include sleep apnea, reflux, urination, palpitations, et cetera. Early morning awakening is often a symptom of depression.

Then you address those things that interfere with sleep. Why are they having trouble falling asleep? Are they having intrusive symptoms? Obsessiveness? Is it generalized anxiety? Hyper arousal? Is it post-traumatic stress? You want to address whatever it is that contributes to that and work your way down the list of what helps a person to recover better.

Dana Parish: What are some of the drugs that you use for people who are having trouble falling asleep?

Robert Bransfield: One thing to add is narcolepsy. You also see sleep apnea. You see behavior disorders. You see sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations. All those things.

In terms of drugs, I might start with something like Trazodone that promotes deep sleep and there are a lot of approved sleep aids that don’t promote deep sleep. Only Xyrem and XYWAV waves promote deep sleep and those are approved for narcolepsy or idiopathic issues. So, it is difficult getting those approved for any off-label use. That’s impossible. A lot of the time you’re using things that are just meds that we know—through research—help with promoting deep sleep. Sometimes traditional sleep aids can help. It depends on what the problem is with sleep and addressing it. Then a part of it might be a sleep disorder i.e., it isn’t just trouble sleeping, it’s a circadian rhythm disorder.

Part of it is being able to be awake during the day. Sometimes you might do something that’s promoting wakefulness during the day—like wakefulness-promoting agents—where you normalize the sleep cycle. Normally you go to sleep, you get deep restorative sleep, and then you jump out of bed ready to attack the world. Normally, people get a slump at four in the afternoon and that occurs as it’s part of our natural bio rhythm. If you’re in Europe, you take a siesta. If you’re in England, you have tea and crumpets. If you’re here in the US, you might have a Starbucks and you just push through it. But if you had a lack of sleep the night before, then you might have more trouble. And also, the people that have sensory flooding, often have a reversed sleep cycle. Daytime stimulation is too much, so they become night owls.

Dana Parish: They see that a lot with kids too, with PANS and PANDAS. Do you think that’s more common in kids? I hear from parents all the time! Their kids sleep during the day and then they’re up the entire night.

Robert Bransfield: Well, it’s easier for kids because they don’t have to be in the office at nine o’clock to work. Plus, the pandemic promoted a lot of bad habits in people and social isolation. I hated the phrase “social distancing.” It should have been called “physical distancing,” not “social distancing.” We need social connectedness during a crisis, not distance. But children can do that. I think they stay up with their cell phones, or send text messages, or play computer games, et cetera. And the light exposure is an added thing that could be contributory.

Dana Parish: One of the things that I found really interesting in conducting so many interviews with patients for our book was the number of times people with Lyme and other infections were thrown into psych wards. Some of them went on to become physicians. Many of them did not get a proper diagnosis or treatment until after they were released and somehow either a parent or somebody stumbled upon some literature that said that different infections could have caused their symptoms. How commonly do you think psych wards and prisons are filled with people that have undertreated brain infections or untreated/unrecognized infections?

Robert Bransfield: There is a study from the Czech Republic that showed that a significant percent of those people (incarcerated or inpatients) tested positive for Lyme compared to the general population in the same area. And it was a spectrum of different conditions. It wasn’t just bipolar; it wasn’t just schizophrenia. It was a whole spectrum. But that’s what you see. It depends on what the genetic susceptibility of any given person is, what symptoms they may manifest. Now, you can’t say they don’t have psych symptoms, they do have psych symptoms, but it’s not mimicking. You just have to understand the etiology of the psych symptom. So, then the patient may show the symptom, and doctors may treat the symptoms, but they’re not addressing the initial etiology of the symptoms or the illness. It’s very prevalent. I’m in New Jersey. New Jersey was number one for the number of Lyme cases in 2017. When the study was repeated in 2021, it was still number one.

Dana Parish: That was where I got infected. In New Jersey.

Robert Bransfield: There are a lot of areas which are supposedly not so prevalent, but probably are. And there may be other strains of Borrelia. They aren’t necessarily Borrelia burgdorferi—i.e., the B31 strain from Shelter Island laboratory strain that’s used as the reference point. It may be Babesia (or another) Borrelia or some other infection that’s contributory, or something that’s unknown that we still have to figure out.

Dana Parish: We should talk about the testing because you just mentioned it and I think that most people do not know how poor Lyme testing is, how inaccurate most of the Lyme testing is. Can you talk a little bit about how a doctor that’s new to the subject should understand this?

Robert Bransfield: If I get a patient that says they might have AIDS, I can do a test and it’s pretty reliable. If I get a patient and they might have Lyme, I can do a test, but the AIDS test is 500 times more reliable than the Lyme test. Importantly, the Lyme test was never standardized for late-stage disease. And if it’s a positive test, it doesn’t mean you have it. And a negative test doesn’t mean you don’t have it. There are a huge number of variables. It could be a different strain of Borrelia that the test wasn’t standardized by. And Lyme causes immunosuppression, so how can you use an immune-based test with an infection that causes immunosuppression? Plus, the Dearborn criteria is skewed. Additionally, a lot of people confuse the surveillance criteria with diagnostic criteria, even though the CDC has the disclaimer saying otherwise.

“The Lyme test was never standardized for late-stage disease. And if it’s a positive test, it doesn’t mean you have it. And a negative test doesn’t mean you don’t have it. There are a huge number of variables.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

If you look at the usual way Lyme is tested, there are not adequate warnings with the commonly used lab test that surveillance criteria picks up 30-40,000 cases a year. Yet the CDC with their own study showed that there were at least 476,000 cases a year. So, the test picks up less than 10%. There’s one study that showed that 3.4 million Lyme tests are done per year. That means it’s a 10:1 ratio for every hundred times. The doctor says, “Gee, this could be a Lyme case.” He sees a positive test once, and a lot of doctors make the mistake of thinking, “We’ll do a Lyme test and if it’s positive you have it. If it’s negative, you don’t.” And that’s not how you assess Lyme disease! You have to do the total clinical assessment. You can’t be lazy and do a test that’s so poorly standardized.

The two tier test has less than 50% reliability and it was never standardized for late-stage disease. So, there are many, many variabilities that make the current test worthless. Yet, if you were to really make it clear this test is very flawed, then a whole body of research is wiped away, which should be wiped away because it was based on a flawed foundation for diagnosis.

Dana Parish: Yes, absolutely.

So, you have to look at how you define it. And when you look in general medicine, if you have chest pain, and I said, “Well, I’ll do an EKG, and if it’s negative, you’re not having a heart attack, but maybe your enzymes are elevated?” No, you have to look at the total clinical assessment. You can’t look at one test alone. Where in medicine do we do that where it’s valid? You have to look at everything. And especially when the testing is of questionable value. You have to do a total clinical assessment.

A lot of people are invested more in the testing and get patents from the test. There’s a bias towards giving inordinate weight to testing that’s flawed. I think that’s a big part of the problem. And I think that in a lot of infectious diseases, they’re used to having tests that are more reliable. So, they do the test and that says what it is or what it isn’t, and then you go from there. But you can’t think that way with Lyme disease, or with these tick-borne diseases. You have to think differently, and people have trouble adjusting to that. And how many infectious disease doctors do proper cognitive and psychiatric assessment that you have to consider in making a diagnosis? Zero. Or I guess some might. But do they have the time for it with the way our healthcare system is with certain economic systems? You have to see a patient every eight minutes or something like that. So, a lot of times you do the test, you don’t have time to do a clinical assessment. So, that part is the failure, how our system’s design prevents us from doing something that really requires a lot of thought.

“There’s a bias towards giving inordinate weight to testing that’s flawed. In a lot of infectious diseases, doctors are used to having tests that are reliable. So, they do the test and that says what it is or what it isn’t. But you can’t think that way with Lyme disease, or with tick-borne diseases. You have to think differently, and people have trouble adjusting to that.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

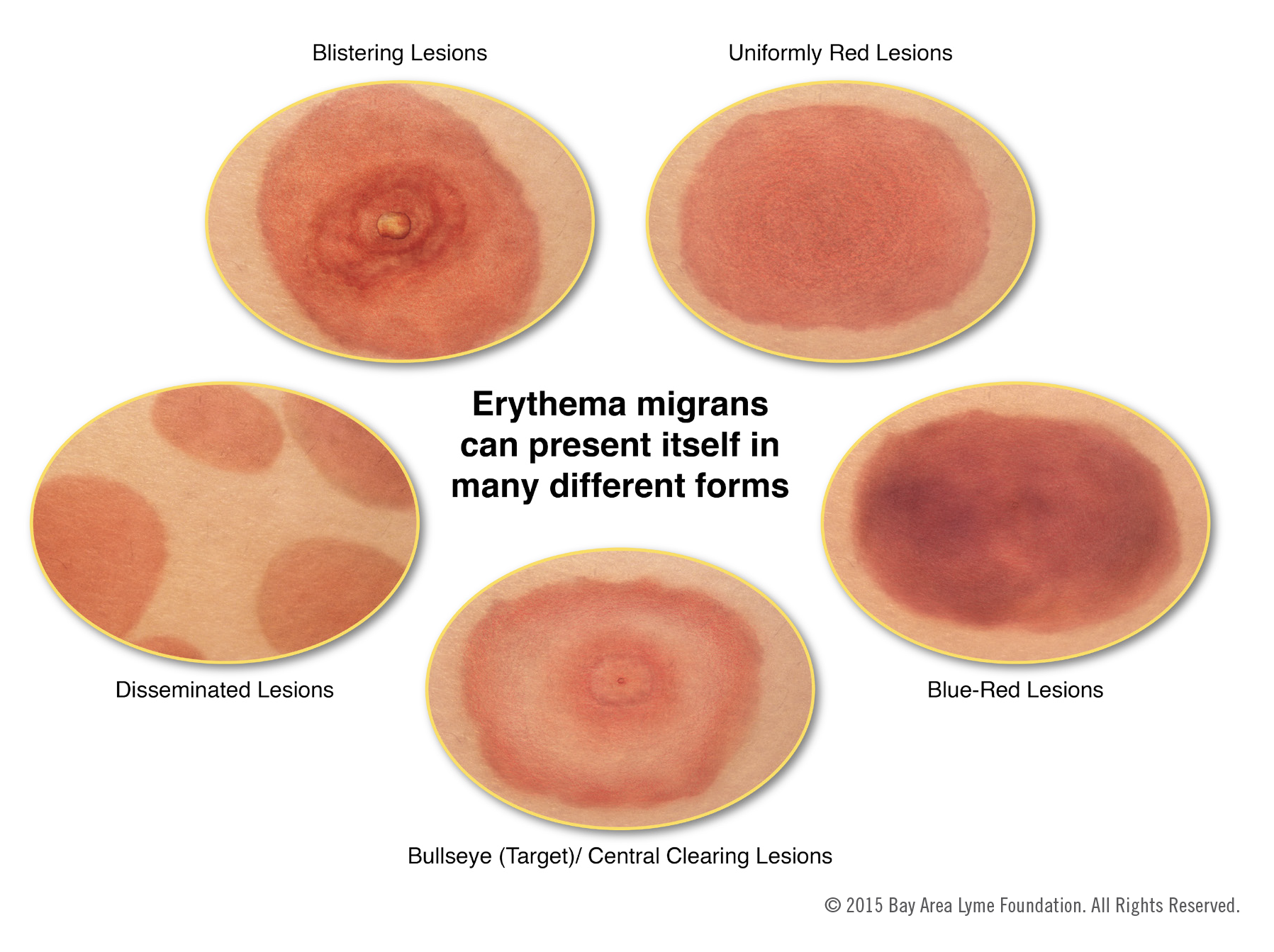

Dana Parish: You’re making me remember something. It didn’t feel relevant until now, but I think it’s important. Doctors are really pressed for time. I was so sick after I got Lyme and I was treated for three weeks with doxycycline. I had a bite and a bullseye rash, and I was treated within a few days of my bite. So, again, there’s this dogma about if you’re treated really quickly, you don’t go on to have chronic infections. That’s completely untrue. In many, many cases like mine, I went to three infectious disease doctors and one of them, although he was part of NYU, was also a concierge doctor. This might be too fancy of a word, but I paid a significant amount of money out of pocket to see him. He was supposed to be so great.

I asked this doctor if he thought this could still be a result? I had tons of symptoms, rashes, trouble breathing, all kinds of new joint pain, visual problems, every single thing in the book. Do you think that this could be still from that tick bite? I knew nothing at the time. I knew nothing. And he said, ‘“No.” I asked why not? And he said, “Because I went to medical school.” That was his answer. And then I pressed him further. I asked: “But there has to be some reason why you’re saying that I was totally healthy before my tick bite and now I’m falling apart at the prime of my life.” He said, “Well, Lyme is killed a hundred percent of the time in the test tube with doxycycline. You took three weeks of it, you are cured.” He wouldn’t evaluate me for any other vector tick-borne diseases… And I did end up having Bartonella as well. I did ultimately go into heart failure because all of these doctors literally just told me—without any exploration—that it wasn’t Lyme and that was it. And I’ve never been treated that way before. What is that?

Robert Bransfield: Well, you can’t say what it’s not unless you know what it is.

Dana Parish: Okay.

Robert Bransfield: And he did not give an alternative diagnosis. So, let’s talk about what happened with that doctor.

There’s this one crazy study where you take just one or two doses of doxycycline, for a tick bite, that’s outrageous. It’s ridiculous. And I see the cases, I see the failures of that. If those things work, my average patient is usually (sick for)10 years, and they get these problems and with those studies they never looked 10 years later to see if that really prevented disease development? And then when they look at the psych symptoms, they say, “This is subjective, nonspecific aches and pains of daily living, so therefore we can ignore them.” That’s irresponsible. It’s negligent when you think of it. Yes, I went to medical school, but what I’m talking about now, I didn’t learn in medical school. I learned from my patients, and your doctor should have learned from his patient, which he failed to do.

Medicine is constant education. We learn from our patients. If something doesn’t make sense, then we have to change our theory and not hold onto a theory that’s invalid and doesn’t apply. He failed to do that and he couldn’t think outside the box.

You can see that some people are black and white thinkers. Whereas in a lot of medicine, you have to weigh shades of gray. When you’re dealing with a complex, evolving, poorly understood disease, you have to think outside the box. You have to weigh contributors and explain something that wasn’t explained before. And was it laziness on his part? Or was it rigidity?

Dana Parish: For me, for my experience, I saw a dozen doctors before I got to Dr. Phillips. I found it was just incredible dogma and rigidity. But it was a knee jerk response. And there was often a smirk accompanied.

Robert Bransfield: Yes. I’ve seen a smirk in depositions.

Dana Parish: What the hell is that? It’s insane. As a patient innocently sitting there saying, “Well, I’ve heard that Lyme could make you sick for longer than 21 days and that people who are on doxycycline … it doesn’t always work.” You see a smirk. And I was actually told in urgent care, “Don’t Google Lyme disease.” When I first went to urgent care, I went because I had the bullseye rash. It was a Saturday. I was told not to Google Lyme because they don’t want me to be biased and swayed by all the crazy Lyme people. And I had never even heard of a crazy Lyme person. What kind of a thing is that to even say?

Robert Bransfield: Well, let’s remember the Osler quote of “The greater the ignorance, the greater the dogmatism.” You have to move forward in medicine, and you have both innovators and laggards. He was a laggard, and he was someone who wasn’t moving forward. I also think you have some that propagate false information for whatever reason.

Dana Parish: Right.

Robert Bransfield: Then I also think you have rank-and-file doctors in the community who take things at face value and don’t do their own research and assume that that’s the way it is. I think there are two groups, and you probably were dealing with someone like that.

“Medicine is constant education. We learn from our patients. If something doesn’t make sense, then we have to change our theory and not hold onto a theory that’s invalid and doesn’t apply. Some people are black and white thinkers. In medicine, you have to weigh shades of gray. When you’re dealing with a complex, evolving, poorly understood disease, you have to think outside the box.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

I’ve had a patient who went to 57 different doctors, and I was doctor number 58 after terrible experiences. In fact, you don’t usually see people going to as many doctors now as used to be the case. People understand Lyme more, but patients still typically have to go to several doctors before getting the correct diagnosis. And I think it’s the people that are closer to the doctors—sometimes psychiatrists, family doctors, nurse practitioners—who are making the diagnoses. Whereas I think some of the more rigid, medical super specialists sometimes have an arrogant attitude of “How can you tell me something I don’t already know?” And you can tell when you’re hit with something that doesn’t make sense. Do you stop and think and try to explain it? Or do you just get rigid and dig your heels in and discount it?

Dana Parish: There’s a great story that we were told for the book by another psychiatrist named Dr. Preston Wiles. I don’t know if you know him. He worked at Yale for a really long time. He’s a child psychiatrist. And he told us that all the doctors at Yale—the pediatricians—used to have kids with psych problems and they would send them to Dr. Wiles.

Dana Parish: There’s a great story that we were told for the book by another psychiatrist named Dr. Preston Wiles. I don’t know if you know him. He worked at Yale for a really long time. He’s a child psychiatrist. And he told us that all the doctors at Yale—the pediatricians—used to have kids with psych problems and they would send them to Dr. Wiles.

He would end up sending them to Dr. Jones who was a wonderful, wonderful pediatric Lyme doctor in New York, may he rest in peace. And these pediatric patients used to go to Dr. Jones, and he used to get them better. But it was so taboo for parents to be taking their kids to a doctor who treated chronic Lyme—even though the kids were getting better—that the parents would swear him to secrecy and he (Dr. Preston Wiles) would get all the credit for curing these intractable cases of kids with psych illnesses. But it was all Dr. Jones by Dr. Wiles’s own admission—or by his own telling of it. So, I just thought that was a remarkable story. And this went on for years, and years, and years, and they never knew that it was Dr. Jones helping these kids.

Robert Bransfield: When you have that arrogance and failure in the system, then it forces other people to treat the patients that are rejected by that belief system. And when that belief system gets corrected, which I hope it will, then more physicians could fulfill their responsibility and treat these people more effectively.

Dana Parish: How can patients advocate for themselves? Right now, I’m hearing so much from the Long Covid community, and we should talk a little bit about the interplay between Lyme and Covid-19, because I know that there is one, and I’ve seen that you’ve written about it, and I want to talk to you about your experience there. But how can patients advocate with their doctors when they’re being told it’s all in their head? I’m talking about all medicine. I’m hearing it constantly. The stories that I’m hearing feel like chronic Lyme on steroids. How do you suggest patients approach this with their doctors and try to educate them and elicit a more open-minded response?

Robert Bransfield: Well, it can be all in your head. Read the chapter I wrote on gliosis, when there’s pathophysiology that is in your head causing it. But it’s not always in your head or imaginary.

Dana Parish: Well, that’s what I’m saying.

Robert Bransfield: And psychiatrists, we get it three ways. One, someone says it’s all in a head, it’s imaginary, it’s functional, those kinds of lines. The second is there is physiology to it causing the symptoms. And the third is the stress of dealing with the healthcare system where they feel rejected by and traumatized by it. So, those are the three things that we run into a lot. And I think one article I wrote, Psychosomatic Somato, Psychic Multisystem Illness and Medical Uncertainty in that article with Dr. Friedman, we addressed that. Also, females are more likely to get a misdiagnosis of “It’s all in your head.”

Dana Parish: Same complaint. I know that. Why is that do you think?

Robert Bransfield: That the same complaint by a male would be taken more seriously? And then someone said, “Well, I should have brought my husband when I had the exam, so they would’ve taken it more seriously.” It almost always goes back to the idea of hysteria. Females are hysterical and there’s discounting of the symptom instead of thinking about it and trying to understand it when it’s maybe outside that doctor’s ability to understand. It’d be nice if they could just be humble. There’s a new movie out showing the girl that was blessed by the Pope.

Dana Parish: Julia Bruzezze. They did a wonderful job in that movie.

Robert Bransfield: When she was being assessed, the doctor said, “Well, let’s lift her up and drop her on the concrete floor and it will show us if it’s hysterical paralysis.” So, they dropped her, and she fell on the concrete floor.

Dana Parish: A horrific story.

Robert Bransfield: That shows the severity of this mindset, of this rigidity. When something doesn’t fit with your belief system, how do you deal with it? Or do you have an open mind? Do you try to understand it, or do you just force your belief system on someone? I think you have to pick your battles. And I think you have to advocate for yourself about what’s going to be effective. I think there are just some people that are close-minded and maybe you’re wasting your time trying to advocate with those people.

Dana Parish: Do you tell them? Do you say to them, look, I don’t think you’re hearing me. I know this is hard. I know this is difficult. When you’re thinking it’s one thing and I’m telling you it’s the other. Does that work? What’s effective in terms of communication? Because some people tell me, “Look, I’m in a town where there are three doctors in a rural town. I’m not in Los Angeles or New Jersey or New York City where there’s a billion doctors and I can just move on.” How do we get doctors to listen?

Robert Bransfield: Well, I think one reason is to ask why they do not listen. And it’s different reasons for different people. And I think then the other is, well, if it’s not that, what makes more sense?

Dana Parish: Okay, that’s great.

Robert Bransfield: And how can you explain it and how can you treat it? What’s an alternative that’s more effective than that? And because you often see that it’s anything but a Lyme diagnosis.

Dana Parish: Exactly.

Robert Bransfield: Okay, then what is it? If it’s not and they don’t have an answer and that it’s hard to believe—like I said, what it’s NOT—unless they can say what it IS that’s more plausible.

Dana Parish: I always use myself as an example. I was so extreme. I got a tick bite and within a week or two, I had severe, sudden anxiety, depression, and insomnia all three together. I also developed a new case of OCD, and I had never had OCD. In fact, I never really quite understood how OCD worked. You just want to say stop. I know people in my life that I love and I’m like, “Can you just stop doing that?” No, they can’t. Well, now I completely understand. And I also was seeing melting monstrous faces, like The Scream painting, every time I closed my eyes and tried to go to bed, and I was being told it was stress. I was told it was not Lyme, but I was not given any reasonable explanation. Is it fair for patients that have a sudden onset of psychiatric symptoms to go to their doctors and say, “You have to evaluate me for infections”? Is it common? It happened to me. I hear it a lot, but is it common in your world that it really is an infection triggering this?

Robert Bransfield: Well, if you have to force someone, they’ll probably do a sloppy job, and you can just see that you’re wasting your time with that person. Dr. Founda has studied a lot of the central nervous system (CNS). It can penetrate the CNS very soon after infection sometimes. And if you’re bitten in the neck, particularly when it’s closer, you see more CNS symptoms.

Dana Parish: I was bitten right here, right on my shoulder.

Robert Bransfield: Now, some people have rapid development and I think the OCD probably is more of an autoimmune piece rather than inflammatory. And it may have to do with what co-infections you had. Some people take that pattern where you see those symptoms right away. Other people take the pattern where it’s slow and then they may go years and then later, maybe there’s a head injury or a stress and or an auto accident—then boom—symptoms appear. They manifest because their body is no longer keeping the infection in check—similar to the herpes fever blister, or shingles analogy. So, there are a lot of different patterns. And I think asking again what could make sense here? But your problem is, how much knowledge do they have about psychiatry? In some ways, family doctors may do a better job. They have that broader knowledge. They have more psychiatric capability.

I was dealing with an infectious disease doctor recently and he said, “Well, psychiatric illness has no physiological basis. Neurological illness does, but not psychiatric illness.” And my reaction was, “Where did that come from?” Well, that came from what he learned. There was one deposition of a Lyme expert who’s a rheumatologist, and he was asked, “What was your training in psychiatry?” He said, “Well, I had a one-month rotation in a state hospital 45 years ago.” And that’s where it came from. “What ongoing continuing medical education psychiatry have you had since?” The doctor said, “Zero.” It’s unbelievable.

There’s a knowledge gap about how to connect the dots. There’s the old saying: “To know syphilis is to know medicine,” but to know Lyme, you have to know more than medicine. You have to know psychiatry. You have to know psychoimmunology. You have to know epidemiology. You have to know about infectious diseases. You have to know many different fields. Part of it is economics and politics. So, you have to pull together many fields and you can’t only look at it with the “silo” mentality and stay in the one field that you master. You have to venture out and learn the related fields so you can connect the dots. And that’s a big part of the problem. These doctors can’t step outside their training and expand with a disease that needs a broader knowledge base in order to really get a grasp on it.

Dana Parish: It’s astounding. I will hear about the same doctor over and over that will see patients with Lyme symptoms that will never see the pattern. Famously, there’s one doctor in New York City and every time I hear from somebody from New York who’s really mad, who just got their diagnosis after their 20th doctor, he was always the one who told them they didn’t have it. He actually treated a friend of mine, and I looked through her records with her because she was going to sue him. She ended up needing a hip replacement because her Lyme got so severe. He could have actually prevented it years and years prior. She had multiple positive Lyme tests that he never told her about. And in her record, it said, “False positive. Check again in three months.” And sometimes I just have no words for these kinds of things.

Robert Bransfield: Well, it’s interesting how people just get locked in a belief system and once you’re locked in, it’s hard to say, “Whoops, I think I was wrong, and I have to think differently.” That’s the difference between humility versus arrogance in medicine. Some of us can do that and recognize that we really missed the boat on something, and we need to look at it differently. And if I look at how I conceptualize mental illness, in my residency training, we had the concept of the “schizophrenia mother.” There, the theory was that the way the mother interacted with the child was what caused schizophrenia.

Dana Parish: Interesting.

Robert Bransfield: Oh my God, what a horrible theory that was. And telling people that when in reality it was the opposite. What happened was that these children were impaired, and the mothers hovered, because they knew they had to.

Dana Parish: Absolutely.

Robert Bransfield: Wasn’t the other way around.

Dana Parish: It’s devastating hearing these stories. It’s cruel and unusual punishment for a mother to have to hear that. It’s terrible. It doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. Before we go, I want to talk to you about Covid-19 and the overlap with Lyme.

Robert Bransfield: I think on one hand the mistakes you see with Lyme, you see with Covid. Covid does get more money and recognition, but you see the same challenges. Who do you turn to for experts? The frontline physicians who treat it every day? Or the bureaucrats that never treat a single case and who just analyze data.

Dana Parish: Well, we’re not allowed to talk about cheap repurposed drugs. We will let people die for a really long time until there’s a vaccine and a new patented drug. I mean, that’s kind of what happened with Lyme.

Robert Bransfield: We saw the same thing with public health, like prevention and vaccines and treatments, particularly if they’re not FDA-approved treatments. And then you get special interest groups with finances involved, but you have to look at the people who are effective. In the early part, they were people that could think outside of the box and adapt quickly through their clinical observations. And these were the initial thought leaders. But then they were a threat to people because they were a threat to certain economic interests. So, they were attacked. It’s a similar situation to Lyme disease. Now, I think some people had both Lyme and got Covid—a lot of Lyme treatments could actually protect people from Covid. So, people that were under active treatment for Lyme often did reasonably well. Some people who had Lyme and weren’t under treatment got Covid, and that caused their Lyme to relapse, and you saw a reemergence of their symptoms. They might get Bell’s Palsy, or long duration panic attacks, for example. They had symptoms that were part of their Lyme that had been in remission until they got Covid. I also saw a couple of people—and this was more in the early part of the epidemic—where some of the people with a high fever seemed like it may have helped their Lyme.

Dana Parish: Interesting.

Robert Bransfield: The fever may have been therapeutic. Let’s consider the hyperthermia treatment that’s used with Lyme patients. I’ve seen that be effective with some people. Let’s say they have an infected port and then they have a high fever. Their Lyme may improve afterwards, or certain Lyme symptoms would improve. So, those were the patterns that I saw. I’ve seen people in a household where the whole household gets Covid and the person under treatment for Lyme does better.

Dana Parish: Yes, I’ve seen that.

Robert Bransfield: And there are a number of treatments that seem to work.

Dana Parish: But given how asymptomatic Lyme can be and how asymptomatic Covid could be, these are two weird diseases that can just lie there dormant and latent for a while. Is Covid triggering latent asymptomatic Lyme, or Bartonella, or other diseases? What I think I’m seeing is a lot of people who were never familiar with vector-borne diseases get Long Covid and then they get all these symptoms that look like Lyme. And I’ve seen a few of them go and investigate, find out it was Lyme underneath, and then they’ve gotten treated and feel a lot better.

Robert Bransfield: Yes. I think there are other things that get activated, but not necessarily Lyme or tick-borne disease, vector-borne disease. There may be other infections that can also get activated. It seems like what’s going around now with Covid isn’t as bad as before. And the whole naming of it—this bogus term “Post-treatment Lyme” is problematic. Was it adequate treatment? Inadequate treatment? Was it in time? Was it delayed? “Post-treatment Lyme” is a bogus name and “Long Covid” is a truck driver’s term. It’s not a medical term. It’s “chronic.” Or “chronic symptoms.” We could argue whether it’s chronic infection and chronic symptoms, or whether it’s just chronic symptoms without chronic infection—although we don’t know if there’s still persistent infection or persistent infection. But either way, it’s a chronic illness and we need to label it properly.

Dana Parish: Absolutely. Semantics inform treatment. And that has absolutely been the case with Lyme. I wholly object to the term: “Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome.” It is chronic Lyme. It is persistent. Lyme. I can’t say: “Post-treatment Lyme.” That’s where I got off the rails with my treatment early on because that’s what I was told. I took it literally at face value and I kept going back to the CDC website and they said in a few months, people with Post-treatment, Lyme Disease Syndrome usually get better. Well, how about the ones that got worse, like me and millions of others?

Robert Bransfield: Well, I’ve seen thousands of Lyme patients. I wouldn’t be seeing these patients if these treatments worked.

Dana Parish: Of course.

Robert Bransfield: And if that false information wasn’t out there, I wouldn’t see so much of it. And then I could do easier things instead of dealing with these very complicated Lyme cases that somebody screwed up.

“I’ve seen thousands of Lyme patients. I wouldn’t be seeing these patients if these treatments worked. And if false information wasn’t out there then I could do easier things instead of dealing with these very complicated Lyme cases that somebody screwed up.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

Dana Parish: I understand. Well, I know that you’re not taking new patients, but you’ll be able to send me a list of some practitioners that know a lot about the psychiatric manifestations of different infections that maybe I could share with some people. And are there good places that you could point us to where doctors or patients can learn from you and people like you?

Robert Bransfield: Well, I do a list for doctors to learn. I’ve been doing that for 20 some years called Microbes of Mental Illness, and there’s several hundred doctors from 20 different countries.

Dana Parish: How do people subscribe? How do people find these doctors?

Robert Bransfield: Well, that information is for doctors, psychologists, and social workers who work with these patients. But we also have educational programs for psychiatrists. We do a monthly program for psychiatrists that want to learn more and for nurse practitioners and clinicians in general. There are also different programs. For instance, the ILADS program. We’re going to do that and repeat that in Hershey in March. And then there’s the Invisible International Program. And I’m going to be working on the microbes and mental illness thing there. There are a lot of journal articles I’ve written. There are a couple I’m working on right now. So, there are a lot of different videos or programs.

Dana Parish: So, there’s stuff out there and you’re continuing to rock and roll, teaching people. I know that. And thank you so much for your time. Is there anything I missed that you wanted to say or did we cover all the ground in this last hour and a half?

Robert Bransfield: Well, you have to keep an open mind and deal with people that have an open mind. I look at where I was 50 years ago with medicine versus where medicine is going to be 50 years from now, or 10 years from now, or 20 years from now. And what are people in the future going to say about the Lyme crisis? Are they going to look at it like the Tuskegee experiment and say that it was disgusting that those people were just saying, “Well, there wasn’t enough evidence. Let’s do more research.”

I’m sure this will be judged by history as a great failure of our healthcare system, that we didn’t move quickly enough with this, and that people were holding back progress. And as time goes on, we’re better at explaining things that we couldn’t explain before, but things that we knew from clinical observation. Now we have more and more physiology that explains it. But people are locked into their dogma.

“What are people in the future going to say about the Lyme crisis? I’m sure this will be judged by history as a great failure of our healthcare system, that we didn’t move quickly enough with this, and that people were holding back progress.”

—Dr. Robert Bransfield

There’s an old quote that “Science advances one funeral at a time.” I think you have people that are just so locked in and have given misinformation for so long and their reputations are dependent on it. They’re not going to say, “Whoops, I made a mistake. I was wrong and Dr. Jones was right. I was wrong.” No, they won’t say that. But those people will eventually retire. And people that aren’t as invested in misinformation will come along. I think there will be people that will be more open. But it’s a struggle. This is the same struggle with any new idea, be it in medicine or anywhere else. People get invested in old beliefs that don’t work anymore for reasons other than just the accuracy of information. There’s 400+ articles showing an association between these tick-borne infections and psychiatric illness. There’s overwhelming data. And for someone to say that it doesn’t cause it, that’s without any scientific review, and those are peer-reviewed articles.

Dana Parish: It goes back decades.

Robert Bransfield: Right. It’s overwhelming, but for someone who has a belief system, they can’t get outside that belief system.

Dana Parish: Yes.

Robert Bransfield: So, keep doing what you’re doing. It’s good that you educate, legislate, advocate, and sometimes litigate when it’s necessary. That’s how you affect the change. You have to do all those things. Right?

Dana Parish: Absolutely. And getting people like you out there to tell it like it is, to set the record straight is so important. I’m so appreciative of you, Bob. It was great to see you.

Robert Bransfield: Okay. All right. Bye.

Dana Parish: Take care. Bye-bye.

This blog is part of our BAL Spotlights Series. It is based on a transcript from Ticktective, our podcast and video series. To listen or watch the original conversation, please click here. Bay Area Lyme Foundation provides reliable, fact-based information so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. For more information about Bay Area Lyme, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.

Bibliography & References:

American Psychiatric Association:The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults. Medical History. 2015. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890426760 https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.1720501

Sleep disorders in patients with Lyme: Greenberg HE, Ney G, Scharf SM, Ravdin L, Hilton E. Sleep quality in Lyme disease. Sleep. 1995 Dec;18(10):912-6.

Study from the Czech Republic that showed that a significant percent of those people (incarcerated or inpatients) tested positive for Lyme compared to the general population in the same area: Kříž B, Malý M, Daniel M. Neuroborreliosis in patients hospitalised for Lyme borreliosis in the Czech Republic in 2003 – 2013. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2017 Fall;66(3):115-123. English. PMID: 28948805.

Chapter that Dr. Bransfield wrote on gliosis: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346327244_PET_Imaging_of_Microglia_Activation_and_Infection_in_Neuropsychiatric_Disorders_with_Potential_Infectious_Origin

Additional articles:

Webpage: www.MentalHealthandIllness.com

PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Bransfield+R%5BAuthor%5D

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9326-6478

Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert-Bransfield

Sci Profiles: https://sciprofiles.com/profile/452253

The following is a list of peer-reviewed articles that support the evidence of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases associated with neuropsychiatric illness.

Autism and the Lyme Disease Connection

Autism and Lyme Disease http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleID=1733709";s:7:"pubdate";s:29:"Wed

The Link Between Lyme Disease And Autism http://www.publichealthalert.org/link-between-lyme-disease-and-autism.html

The Lyme-Induced Autism (L.I.A.) Foundation http://www.lymeneteurope.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=2563#p18713

90% of kids with autism have Lyme?? http://www.lymeneteurope.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=661&start=10

Lyme Induced Autism part 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6n14D9Qtc9s

Lyme Induced Autism part 2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJtCTpbj3FE

Our Lyme / Autism Story https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4X2LdQmHrY

Dr. Horowitz speaks on the Lyme Autism connection https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHwHXF_v52Q

Dr. Jones speaks on the Lyme Autism Connection https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NoEsgLyN2-0

The Connection between Lyme & Autism http://lymediseasechallenge.org/lyme-autism/

TOUCHED BY LYME: Unraveling the Lyme-autism connection https://www.lymedisease.org/lyme-autism-connection/

THE AUTISM AND LYME DISEASE CONNECTION http://restormedicine.com/autism-lyme-disease/ Doctors Find Link Between Lyme Disease, Autism http://www.foxnews.com/health/2011/09/27/doctors-find-link-between-lyme-disease-autism.html

Toxoplasma Gondii Infection and Aggression in Autistic Children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal https://journals.lww.com/pidj/Fulltext/9900/Toxoplasma_Gondi_Infection_and_Aggression_in.57.aspx

Here’s some things Dr. Jane Marke pulled off her website. Tessa Gardner wrote a long chapter in the textbook of infectious illnesses during pregnancy, and every year it’s become smaller and smaller, and she’s been taken off it:

- Tessa Gardner chapter part 1, part 2, part 3 and part 4 about the impact of Lyme disease on the fetus of pregnant women who are infected with it.

- www.lymediseaseguidelines.org provides arguments and references by health professionals which illustrate why current guidelines are dangerous.

Mothers Against Lyme resources:

- Gestational Lyme Studies, by Charles Ray Jones, M.D., Harold Smith, M.D., Edina Gibb, and Lorraine Johnson, JD, MBA

- Course and Outcome of Erythema Migrans in Pregnant Women, by Vera Maraspin, Lara Lusa, Tanja Blejec, Eva Ružić-Sabljić, Maja Pohar Perme and Franc Strle.

- Congenital Infections in Pregnancy, Dr. John Lambert, Full Professor of Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Mater Hospital and UCD, Dublin.

- A systematic review on the impact of gestational Lyme disease in humans on the fetus and newborn, Lisa A. Waddell, Judy Greig, L. Robbin Lindsay, Alison F. Hinckley, Nicholas H. Ogden.

- Mothers Against Lyme letters: We have already demanded that the National Institute for Health (NIH) begin research on both congenital and pediatric Lyme disease. Letter to Director of NIH and The NIH’s Response. We also demand that The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) add Lyme disease to its list of congenital infections deserving of research money.

- Mothers Against Lyme Calls for Retraction of False Information on Congenital Lyme in IDSA, AAN, ACR Guidelines NEW YORK, NY, November 9—Mothers Against Lyme, a group of advocates concerned about the impact of Lyme disease and its co-infections on pregnant women, children and families, is calling for retraction of a statement in the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease that contributes to misdiagnosis and harm to pregnant women and children who are congenitally infected. Retraction request cites harm to pregnant women and children. Read More