– Wendy Adams, Research Grant Director, Bay Area Lyme Foundation

Erythema migrans (EM) is the hallmark sign of infection with B. burgdorferi. An EM is defined as an expanding annular (round) lesion or rash of at least 10cm (2.5in). Most rashes occur 3–30 days after infection, however there are case reports that show EMs can appear sooner than three days post infection.

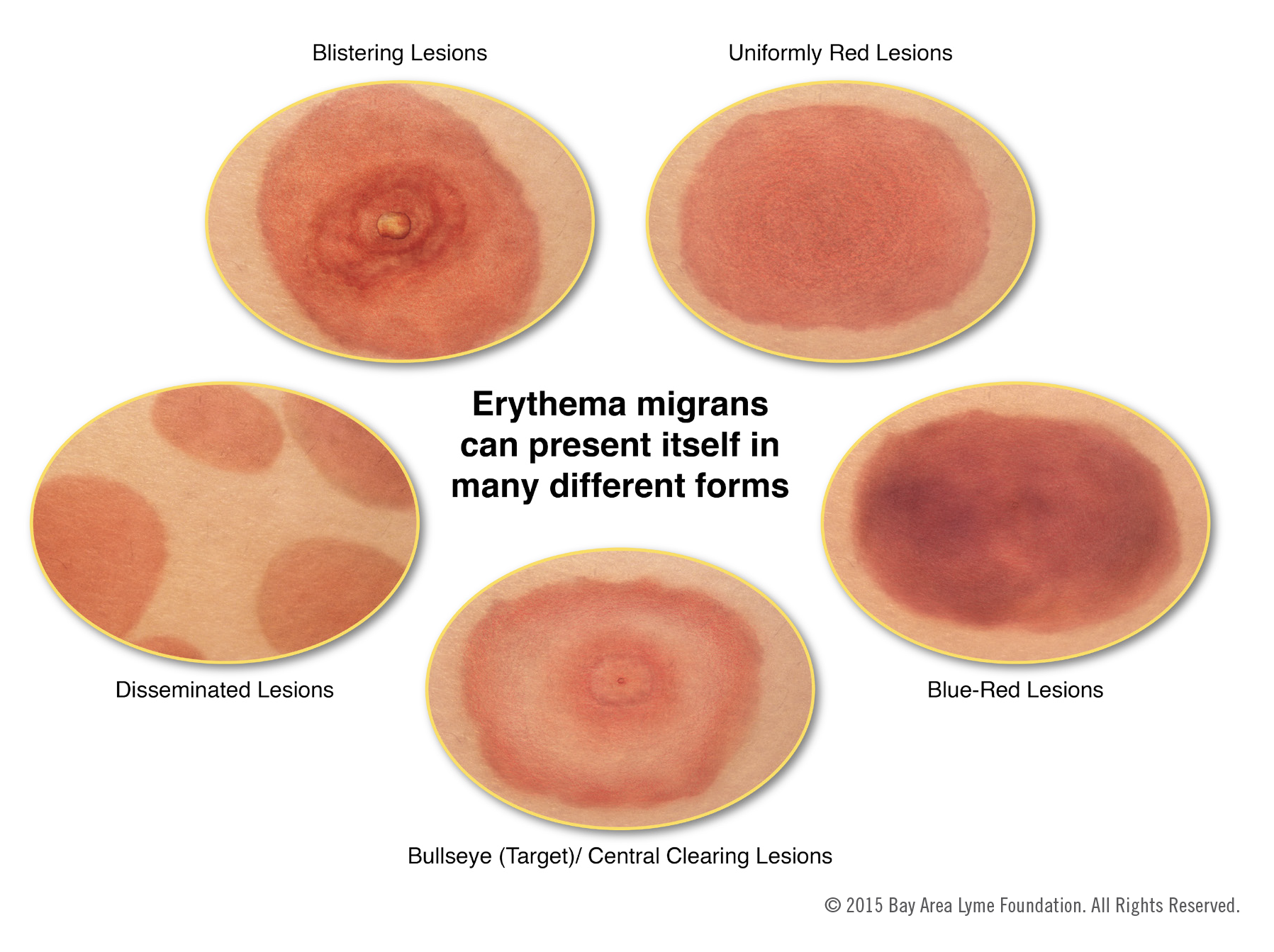

The term “bullseye” rash is often used synonymously with EM. But an EM is not required to have central clearing or a target appearance. The rash can take many forms, and may have a raised bump in the middle, can be itchy or warm, and can have a bluish cast like a bruise. It can be round or even oval. Only 20% of Lyme disease with an EM have the bullseye presentation. That means that only 1 in 6 total Lyme cases will have a rash with a target appearance.

The rash also may not be present at all. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that 70-80% of patients may exhibit the erythema migrans, this number can vary by study. For example, a 2010 study showed that in the state of Maine only 43% of Lyme patients exhibited this rash when infected with Lyme.

If you develop a rash, the best thing is to document it—take a picture next to a ruler so you can determine the size. This can be very helpful to a healthcare provider in evaluating the rash. You can also draw a ring around the contours to see if it expands over time.

If you see multiple EM rashes (these can form close to the original rash, or in other places) this indicates a disseminated infection. Again, take a picture of the rashes and get in touch with your healthcare provider immediately. Disseminated infection means the infection has circulated in your body and could be present in the brain, the heart and/or the joints. Immediate treatment with antibiotics is important to prevent more severe complications of infection, like Lyme neuroborreliosis or Lyme carditis.

The chart below illustrates several of the forms these rashes might take (see the CDC website for more examples).

Image courtesy of Emily M. Eng

Image courtesy of Emily M. Eng

EM’s have varying presentations and are even more difficult to diagnose on people with darker skin color. More info here.

Lyme has confusing symptoms both before and after treatment. Even simple undisputed facts, like the definition of an EM, are routinely misunderstood and miscommunicated by the physician and science community.

Mischaracterization of an EM as a bullseye rash is widespread. Official NIAID reports on Lyme disease, FDA notifications, peer reviewed papers in major journals, Harvard Health webpages—all have equated an EM with a bullseye rash. Even a recently published textbook, edited by department chairs at Brigham and Women’s and Tufts Medical states that an EM is a bullseye rash. Often an EM with no central clearing is misdiagnosed as cellulitis, a bacterial infection involving the inner layers of the skin, or even diagnosed as a spider bite. Patients are either sent home or prescribed a class of antibiotics that are not effective against Lyme disease.

Almost a dozen cases of acute Lyme fatalities have been published in the last few years. Most have a common theme—patients present multiple times to their PCP or ER with characteristic Lyme symptoms during an endemic season, which are dismissed as viral or idiopathic. Even disseminated EM’s are being mischaracterized, or worse, diagnosed as Lyme and then not treated. These patients are then either found dead at home, or deteriorate and die in the hospital because they have not been treated in time. Other tick-borne infection case fatalities from misdiagnosis are published as well.

Diagnosing patients early is the best way to protect someone from life threatening Lyme complications. When only one third of patients present with a known tick bite, the rash is not seen or mischaracterized and the test is less accurate than a coin flip, all we have are providers’ diagnostic skills. Improved testing, a major focus of Bay Area Lyme Foundation’s research efforts, will ensure less room for human error in the timely diagnosis of Lyme and other tick borne diseases.

Yes, interested in following up on this and continuing to play some small but hopefully useful part in learning more about Lyme diag and tx.

Gerry

I live in Ontario and was bitten by a tick in late March. I woke up 5 weeks later and had a rash all over the left side of my face and down neck. The side that I was bitten by the tick in my hair, on top of head. I also had Bell’s Palsy and terrible headaches for weeks, muscle weakness, pain, trouble speaking, and lots of angry outbursts and itching in my head. Took antibiotics for three weeks and now (August) still suffering. Hard to get help and to cope. Forgetful too and hard to find the words to describe things.