Ticktective Podcast Transcript

Ticktective™ host Dana Parish interviews Scott P. Commins, MD, PhD, about the growing prevalence of alpha-gal syndrome, a food allergy condition caused by a tick bite, where people develop an allergic reaction to a sugar found in red meat and other mammalian products. Symptoms can include hives, gastrointestinal distress, and potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis, often occurring 3–6 hours after consuming specific foods. This syndrome is increasing, especially in the Southeastern United States, due to the spread of the Lone Star tick. Dr. Commins discusses the current state of research in the US and how investigators are working to develop immunotherapy approaches to help desensitize patients and potentially resolve the allergy over time.

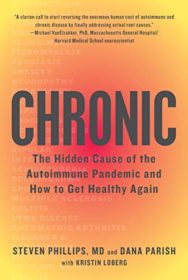

Dana Parish: Welcome to the Ticktective Podcast, a program of the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, where our mission is to make Lyme disease easy to diagnose and simple to cure. I’m your host, Dana Parish, and I’m the co-author of the book Chronic, and I sit on the advisory board of Bay Area Lyme Foundation. This program offers insightful interviews with scientists, clinicians, patients, and other interesting people. We’re a nonprofit based in Silicon Valley, and thanks to a generous grant that covers a hundred percent of our overhead. All of your donations go directly to our research and prevention programs. For more information about Lyme disease, please visit us at bayarealyme.org.

Dana Parish: Welcome to the Ticktective Podcast, a program of the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, where our mission is to make Lyme disease easy to diagnose and simple to cure. I’m your host, Dana Parish, and I’m the co-author of the book Chronic, and I sit on the advisory board of Bay Area Lyme Foundation. This program offers insightful interviews with scientists, clinicians, patients, and other interesting people. We’re a nonprofit based in Silicon Valley, and thanks to a generous grant that covers a hundred percent of our overhead. All of your donations go directly to our research and prevention programs. For more information about Lyme disease, please visit us at bayarealyme.org.

Today, I welcome Dr. Scott Commins. He is a highly esteemed expert in the field of allergy and immunology at the University of North Carolina (UNC) and a pioneer when it comes to alpha-gal syndrome. You’ve heard about alpha-gal when a tick bite can cause a meat allergy, but there is so much more to know. So enjoy this interview. I hope you learn a lot and please share it with your doctors because there is such a lack of education about this very important syndrome, and doctors becoming aware of it will only help us patients.

Dr. Commins! Thanks for joining us today. I’m so excited to finally meet you. For so many years, I’ve heard about you, the legendary work you do, and all the patients you help with alpha-gal syndrome. You are the number one expert in my world, so thanks for everything you do. I just heard something so cool about you. I heard that you now have the William J. Yount professorship at UNC. Who was he, and what does this mean for you?

Scott Commins: Very exciting. It just happened within the past year when I came to Carolina about 10 years ago. They put my clinic on a Wednesday, and it turns out that’s the academic day here. So there were very few people seeing patients in the allergy clinic, but the one other person at that time was Dr. Yount, and he was the founding member and faculty member of the rheumatology, allergy, and immunology division at UNC. And he did this amazing basic science work and in sort of this full life full circle moment, one day Dr. Yount and I were chatting between patients and it turns out that he had been in London training on a new technique that was taught to him by my mentor, Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, who was the senior person in the lab in London at the time. And so it was this kind of amazing moment as though my two mentors had connected. And so, holding the Yount professorship is incredibly meaningful to me.

Dana Parish: Congratulations.

Scott Commins: Thank you.

Discovery and origins of alpha-gal syndrome

Dana Parish: If you don’t mind taking us back to the beginning, I know some people have a little burgeoning awareness of what alpha-gal Syndrome is, but in listening to your talks and reading things that you’ve published and written about, I have been shocked at really what alpha-gal can do and what it is. So, if you don’t mind, just what is alpha-gal syndrome?

Scott Commins: Right, so alpha-gal syndrome, which I will probably call AGS, and I can tell you why I feel strongly that we consider it a syndrome, but at its basis, the alpha-gal allergy is an allergic response to a sugar. And the sugar is galactose alpha one three galactose, which we abbreviate alpha-g for short. And it’s a really interesting sugar, scientifically, because as humans, we don’t have this sugar. We have a premature ‘stop code’ on in one of our genes that would make this sugar, but it doesn’t. And uniquely, all lower mammals, so non-human, non-primate, cows, pigs, cats, dogs, all non-human primates have alpha-g. Immunologists have known about the sugar for a long time because we as humans make a response to it. We don’t make the sugar; we make an immune response to it, and it is the reason that if you were to say, put a pig liver in me, I would hyperacute reject it is what they call. So, we have all these antibodies directed against alpha-gal.

“At its basis, the alpha-gal allergy is an allergic response to a sugar.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

So, the transplant surgeons have known about it for years. But what makes the alpha-gal syndrome unique is now we’re talking about people who’ve developed an allergic response—not an infection-fighting response—but an allergic response to alpha-g. So when they eat red meat like beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, et cetera, non-human mammal meat, then they get an allergic reaction. And it can be the typical kind of allergic reaction where you get hives or itching or swelling, shortness of breath, chest tightness, lightheadedness, right? We think about anaphylaxis; you can have that with alpha-gal syndrome, but uniquely, it’s delayed. So you eat a burger or a hot dog for dinner, and nothing happens for hours. Then 3, 4, 5, 6 hours later, you start to itch, and then it progresses from there. So, it is unique in a lot of ways. It’s a sugar, and almost everything else about allergy is based on proteins, and the reactions are delayed.

So, the transplant surgeons have known about it for years. But what makes the alpha-gal syndrome unique is now we’re talking about people who’ve developed an allergic response—not an infection-fighting response—but an allergic response to alpha-g. So when they eat red meat like beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, et cetera, non-human mammal meat, then they get an allergic reaction. And it can be the typical kind of allergic reaction where you get hives or itching or swelling, shortness of breath, chest tightness, lightheadedness, right? We think about anaphylaxis; you can have that with alpha-gal syndrome, but uniquely, it’s delayed. So you eat a burger or a hot dog for dinner, and nothing happens for hours. Then 3, 4, 5, 6 hours later, you start to itch, and then it progresses from there. So, it is unique in a lot of ways. It’s a sugar, and almost everything else about allergy is based on proteins, and the reactions are delayed.

So that makes it tough to diagnose, and it changes. When we figured this out, it really changed the paradigm for food allergy because typically you would tell someone, look, if you’ve made it to your teenage years safely eating a food, you’re probably good to go. Your immune system has seen that food countless times; it’s not making an immune response. Yes, there are occasional episodes—I would call it rare of adult-onset food allergy, but that does occur. Seafood we hear about, but we really haven’t seen these massive numbers of people becoming allergic to a brand new allergen as an adult as we’ve seen with AGS. So it has changed that paradigm of: once you tolerate something, you’re good to go. Alpha-gal has flipped a lot of our conventional food allergy rules on their head.

Dana Parish: So, where did this originate? When did science first discover this happening?

Scott Commins: The origin story is kind of long and unique, I think, but basically in the lab of Dr. Tom Platts-Mills at the University of Virginia, his group was working on and investigating patients who were actually in the cancer clinics and they were reacting on first infusion to a chemotherapy drug called Cetuximab. And when you want to get an allergist interested, often it’s that idea of a first infusion. So these are cancer patients who’d never seen this drug before. The first time they get it, they’re having these allergic reactions. So for an allergist, you start to think, wait, that allergic response is already there. It’s not something that happened after the immune system saw this medicine multiple, multiple times. It was already there.

Dana Parish: Because that’s the normal thing. You get primed for these things, and then it happens. You get your first bee sting, and maybe nothing happens. You get the second one, and oh my God, my whole face is swollen or whatever.

Scott Commins: That’s right. We see real penicillin allergy in patients who receive penicillin over and over again. That induces the immune response. But this was unique in that first infusion. So Dr. Platts-Mills’s lab really in collaborating with others was the place that figured out the patients who were reacting to Cetuximab were reacting to this alpha-gal sugar that is on Cetuximab. It’s placed there because they’re made in a mammal cell line.

Dana Parish: This is a monoclonal antibody, correct?

Scott Commins: That’s right. It’s not uncommon for pharmaceutical companies to make these monoclonal antibodies in a production cell line. That’s the usual business. But this just happened to be one of those instances where the cells put a lot of copies of this alpha-gal sugar on the final version of Cetuximab. And so patients were reacting on initial infusion, and the UNC experience was pretty heavily documented where they started a clinical trial, and the first two patients that they gave Cetuximab to both reacted, one had severe anaphylaxis and I think ended up needing to go to the hospital for further treatment. So it was happening at a rate in some places, and that becomes key in some places, probably in the 20 to 40% range. But there were other places, like Boston and California, where it wasn’t happening at all.

Dana Parish: That’s so interesting.

Scott Commins: Yeah, so there became this sort of geographic portion to the story as well that became a paper in the New England Journal.

Dana Parish: What may have been happening was that they were primed, and they didn’t have any symptoms, and then they got this second hit, and it was like, ‘Oh gosh, I might have anaphylaxis!’

Scott Commins: That’s right, but we didn’t know anything at that stage about bites. There was no sense of red meat allergy or the whole AGS thing. It initially started as basically a drug allergy, and then right on the heels of that, Dr. Platts-Mills’s group figuring out that these patients all have an allergic antibody that recognizes this alpha-gal sugar around that same time. Then I joined his group, and we started to hear from a very small number of patients: ‘I think I might be allergic to beef, but it’s weird because it doesn’t happen every time. And then I was worried about beef, so I cut it out, and now I think it’s happening to pork.’ And so basically what the patients end up describing in the allergy clinic, mind you, not the cancer clinic, but in the allergy clinic, was that they were allergic to mammal meat. We were fortunate that his lab had been thinking about alpha-gal already. So it started to make sense like, wait, could the distribution of this alpha-gal sugar explain what these patients are telling us in the allergy clinic? And his lab happened to have the test because they’d been working on it for the Cetuximab story. As you might think, I would just draw some blood and let’s run these meat-allergic patients’ blood tests for the alpha-gal allergy and see what happens. And sure enough, they were positive.

It’s sort of, I think, in many ways the serendipitous story. I think we probably would’ve figured it out. I sense that we figured it out much quicker because of what Dr. Platts-Mills’s group had already been doing. When I landed in his lab, basically that becomes my project that is this: ‘Hey, doc, I think I could be allergic to beef.’ And then sort of explaining it from there. So in 2009, we published the first report in the US, just two dozen people, 19 from Central Virginia and five from southern Missouri, all tested positive by blood tests for alpha-gal IgE, which is the allergic antibody. And that was a report at that time. We had not formally challenged them in an ‘Eat red meat, let’s see what happens’ kind of thing. So it was just the report, and that was 2009, and it has just continued to expand and widen since that time.

Dana Parish: Is this still happening with monoclonal antibodies or any other biologics?

Scott Commins: I think the short answer is that it is not a concern. I think the pharmaceutical companies have learned now to screen for some of this stuff that happens after the sugars kind of go on last, and so they sort of screen now for what happens at the end. And I think it could happen again, sure, but I think it would be really unlikely to see this kind of story play out again, is my sense.

Relationship between alpha-gal syndrome and tick bites

Dana Parish: Interesting. So the most common way that people acquire alpha-gal syndrome is through tick bites—it sounds like that’s what you’re saying.

Scott Commins: Yes. We had no knowledge of tick bites as all this started, but we’ve now established, both in mouse models in the laboratory and then in a case-control study with the CDC, that tick bites are the risk factor or are a risk factor for developing alpha-gal syndrome. In the US, the tick species of most concern is what we call the Lone Star tick or Amblyomma americanum. It turns out that alpha-gal syndrome is worldwide. And it is fascinating to me that in each of these places where there are hotspots, Europe, Scandinavia, Australia, and South Africa, there are ticks, and there are different species of ticks in these places. So in the US, we worry a lot about Lone Star ticks, but it’s not at all just a Lone Star tick phenomenon.

Scott Commins: Yes. We had no knowledge of tick bites as all this started, but we’ve now established, both in mouse models in the laboratory and then in a case-control study with the CDC, that tick bites are the risk factor or are a risk factor for developing alpha-gal syndrome. In the US, the tick species of most concern is what we call the Lone Star tick or Amblyomma americanum. It turns out that alpha-gal syndrome is worldwide. And it is fascinating to me that in each of these places where there are hotspots, Europe, Scandinavia, Australia, and South Africa, there are ticks, and there are different species of ticks in these places. So in the US, we worry a lot about Lone Star ticks, but it’s not at all just a Lone Star tick phenomenon.

Dana Parish: First of all, is the prevalence becoming greater, and are there geographical hotspots specifically here?

“We had no knowledge of tick bites as all this started.”

– Scott Commins MD, PhD

Scott Commins: There are hotspots here, particularly the middle southeastern states, so I would think North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Southern Missouri have a real problem with this, and Arkansas as well. But now we’re seeing an explosion of cases up the East Coast. In the paper that we did with the CDC and Viracor, we looked at all of the positive blood tests, I should say in the US up until 2022, and 4% of all positive testing was coming out of Suffolk County, Long Island.

Dana Parish: Oh my gosh, I don’t go there anymore. Even if you are the most careful, like me, I walk on the stones in the center of the sidewalk. I mean, I got a tick bite walking into a restaurant cobblestone through big stones. There were a couple of blades of grass that got me on my toe. I’m just saying it’s so hard to avoid. I mean, it’s almost like, are we being punked? There are this many billions of ticks in this area? It’s crazy.

Scott Commins: The story in the Hamptons is fascinating and incredible, but you hear similar things from people who live in northern Arkansas in southern Missouri. The number of ticks is just incredible. So we are seeing up the East Coast, but now there’s movement of this or awareness or just cases of AGS being found in the central US and even some cases sort of headed toward the Great Lakes area. So there are hotspots for sure, and you asked about prevalence. We and others are working on that. But I can tell you from just taking care of patients, I have some people who come in and will say, ‘Look, I think I’ve had this for years. I was finally diagnosed.’ I will equally have people who come in and literally were diagnosed, or we diagnosed them four to six months before. So, new cases are still emerging. Absolutely. And then there are these kinds of more historic cases as well that are just kind of now coming to awareness. So it is a mix, but it’s certainly not all this retrospective idea.

Lone Star ticks and attachment times

Dana Parish: It’s just so weird. I mean, when we wrote the book, I just remember thinking about alpha-gal; everything else seemed sort of straightforward, and I could get a handle on it. The first few years that I was in the Lyme world, I thought alpha-gal was an infection. I didn’t even understand that it was this whole other entity unto itself. It’s so fascinating. I’d also be curious if you could tell people what a Lone Star tick looks like. I know they have identifying features, but could you send them into a lab before you get diagnosed like we do with Lyme, Babesia, and Bartonella? We send the ticks to labs sometimes to find out what was in that tick that bit me. Is alpha-gal on the list of things they can identify?

Scott Commins: Currently, alpha-gal is not on that list. And I think some of this is that on the research side, from an AGS standpoint, I would say we are a decade, or maybe two, behind the Lyme disease researchers because once you initially identify it, then you’re doing all of those more basic things that have to be answered like food challenges to show that it’s delayed. So we currently don’t have the capacity or the ability, I should say, to be able to test a tick, so to speak. For alpha-gal, I think where the data are currently leading us is that most or many Lone Star ticks have the alpha-gal antigen or allergen we think of as part of their salivary compartment, so to speak.

Dana Parish: So that makes tick attachment time very different from what is traditionally thought. There’s a lot of misinformation around this whole topic of whether ticks can transmit anything concerning quickly. So, I think you just said something so interesting.

Scott Commins: Yeah, no, we are fascinated by that. So I’m glad you brought it up because people will often say, ‘How long does the tick have to be attached to me before I should be concerned?’ And I think at the basis, it may be that the allergic response to alpha-gal occurs much faster than what it would take for an infection to transmit, right? This may be a real differentiator between infection-related or infection-associated tick-borne illness and alpha-gal syndrome because, let’s be honest, it is an incredibly difficult experiment to ask a patient to just keep the tick attached, and let’s see how long you can do that. So we’re going to have to accumulate this data, I think, from some of our mouse models, but it seems to me that one of the hallmark parts of the story for people who develop alpha-gal syndrome is that the site of the tick bite is red, itchy, and inflamed. It’s slow to heal, and sometimes people will even say it feels as though there’s a hard knot underneath where the tick has bitten them.

“I would say we are a decade, or maybe two, behind the Lyme disease researchers.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

Dana Parish: I had that. It was itching for so long, and you could see it for so long that I went to the dermatologist two, three months later. It was still red and itchy, and I had a line going all the way down my arm. It was not cellulitis, but it was this weird immune response. Have you seen that before?

Scott Commins: Yes. I think that is kind of like this allergic response that’s happening in the skin to some part of the tick, whether it’s the saliva or ticks use cement to attach or could it be some factor that is part of their… they don’t have heads, they have what people call mouthparts. For some people who go on to develop AGS, what you described is that initial allergic immune response. The way I think about this is a pyramid where you have to have what you just described to eventually go on to develop AGS. But I think there are a tremendous amount of people who have similar reactions to a tick bite but never truly develop the alpha-gal allergy. And this whole area needs more funding and is ripe for research because we don’t understand enough about the human immune response to tick bites to know when people talk about that skin response that you just mentioned, what does that mean and how do we predict from there who goes on to develop alpha-gal syndrome and could we intervene in some way to be able to stop that? So I think if people get that kind of response, I would ask them to be sort of tuned into that. And the tick itself: the differentiating markings on a Lone Star tick are on the female, so they have a white spot on their back. But to me, the male Lone Star ticks look like any other tick. But it’s the females that have that white spot.

Dana Parish: Are they bigger than a deer tick? So just for people who don’t know, a deer tick is often the size of a poppy seed when they’re not engorged; they’re so tiny. That’s why people miss them all the time, like me. Is this tick a little bigger?

Scott Commins: It is, but it also has that larval stage where people will talk about seed ticks. You can get 50 or a hundred bites if you brush by the wrong leaf as these hatch. I can’t differentiate between those larval stages among the various species.

Dana Parish: At that stage, they can transmit.

Scott Commins: It seems pretty clear from talking to patients, and we know from the next stage up, which is the nymphal stage in our mouse model, Dr. Shahid Karim, who’s our collaborator on the tick mouse side of it, he can sensitize mice. He can make them allergic using that middle nymphal stage. So we think probably it goes even to those tiny seed ticks.

Symptoms and presentation of alpha-gal syndrome

Dana Parish: That is so fascinating. If people don’t know that ticks are the dirty needles of nature, take that away from this conversation and avoid it at all costs. We can talk about that later because there are probably a couple of tips that you have for us in terms of the reactions that people are having to alpha-gal. I’m sure there’s a breadth of them, and I’ve heard you talk. I’ve heard many of your talks, so I know that there is, but I’m curious, what is the breadth, what are you seeing, and what do you hear about most commonly in your patients?

Scott Commins: Sure. So the most common presentations amongst my patients are hives accompanied by gastrointestinal distress. So, I think hives need no further explanation. They often seem to start, the allergic reactions seem to start for many people with itchy red palms. And then within 15, 20, 30 minutes, they’ll talk about some more systemic itching and hives and then often gastrointestinal upset. So nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and pain that I’ve heard. I’ve had patients tell me my female patients will say worse pain, more painful than having childbirth. I’ve had patients who’ve had appendicitis say that the pain associated with alpha-gal syndrome reactions is similar. I think it is the type of gastrointestinal pain that can take adults to an emergency department in the middle of the night, which I think says a lot because no one wants to go. Some patients talk about shortness of breath. It doesn’t seem to come up. The respiratory part doesn’t seem to come up quite as much, but certainly, lightheadedness and dizziness, which means that your blood pressure is falling. So, those things go together to create this scenario called anaphylaxis.

“The most common presentations (of the alpha-gal syndrome) amongst my patients are hives accompanied by gastrointestinal distress.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

Dana Parish: Calm people have anaphylaxis, too.

Scott Commins: Well, keep in mind that anaphylaxis technically means you have two organ systems involved. So if you have skin and gastro and you’ve had a likely allergen ingestion that meets the definition for anaphylaxis. So, roughly 70% of people who have AGS have a history of anaphylaxis, which is high.

Dana Parish: I thought it was just like the throat swelling. I didn’t know that. That’s great to know.

Scott Commins: Yeah, it’s sort of a common misconception. But the other part of this that we see and are now in tune with is that some people present with isolated gastrointestinal symptoms, so they don’t get hives or itching or shortness of breath, throat closure, or any of that. Their presentation is that of abdominal cramping and pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. It often is delayed in many instances, more on the two- to three-hour mark than, say, the four- to six-hour mark. But it does not seem to typically happen right away.

Dana Parish: It’s terrifying to think about you having a hamburger or something and you go to sleep two and a half, three hours later and you wake up in this state. It must be so traumatizing and terrifying to know that you’re living with this.

Scott Commins: I think that part is tough on folks and you can imagine if you go to the emergency department in the middle of the night before there being much awareness of AGS, one of the things that we were hearing from patients is that they were being told, well, it can’t be a food allergy because you were asleep. You hadn’t eaten anything in a couple of hours.

Dana Parish: I can’t even imagine that if that happened, anybody would figure that out in an ER unless they were at your hospital. I mean, honestly, I think it’ll be very, very uncommon.

Scott Commins: Raising awareness is a critical piece of what I feel like I do, and so talking to you is really important because to me, sometimes I think that just getting the word out is probably as big a part of what I should be doing as it is seeing patients and doing research.

Dana Parish: I appreciate that there’s so much that people need to do and it’s so complicated, but it’s also so common. The more we can put this out, the better, and hopefully, they’ll share it with their doctors and their family members. A lot of patients, I’m sure you hear this, their family members are baffled by their symptoms. It’s so weird sometimes and so disparate, and they come on at strange times. They migrate and change, and you’re told you must be crazy, but you’re not crazy. Infections do this. Many infections can do this. I heard you say something so fascinating about the relationship between alpha-gal reactions, alcohol, and exercise.

Scott Commins: Sure. In the food allergy field, we have long known that exercise is what I call a bad actor in facilitating reactions. Technically, we call exercise and alcohol co-factors, but there are other food allergy syndromes where they’re exercise dependent, and wheat is one of the classic examples in adults. People eat wheat fine, and they exercise fine, but if they eat wheat and exercise, they can have anaphylaxis. So we’ve seen the same thing in the AGS space where someone may have say, a slice of pepperoni pizza and be fine, but if they’ve been for a run before and maybe have a couple of beers or drinks with the pizza and the pepperoni, now all of a sudden, they react. I’m not sure that we have really worked out the mechanism behind both of those, but alcohol is a vasodilator, so you’re probably increasing allergen absorption from the GI tract.

Dana Parish: Oh, interesting.

Scott Commins: And exercise also would cause vasodilation. So the presumption is you’re pulling more allergen in through the gut through absorption, but we find in addition to alcohol and exercise as co-factors, stress, illness, infection, and lack of sleep.

Dana Parish: I was going to ask you about this

Scott Commins: And for women, menstruation. Other kinds of co-factors can facilitate allergic reactions in general.

Dana Parish: So, in general, would you be more susceptible to even having this syndrome to begin with if you had any sort of immune dysfunction or if you were slightly immune-compromised?

Scott Commins: It doesn’t seem to be in our group. We haven’t seen people who have trouble with immune suppression or immunocompromised that they’re at an increased risk for developing AGS. So I think that, hopefully, is a little bit of good news.

“For alpha-gal, I think where the data are currently leading us is that most or many Lone Star ticks have the alpha-gal antigen or allergen… as part of their salivary compartment.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

Dana Parish: Do kids get it?

Scott Commins: They do. It doesn’t seem like kids get it perhaps as frequently or maybe it’s better said that we don’t have as many kiddos in our cohorts, but certainly, children can get it and when they do, it looks like the adult version so to speak: they get hives and GI distress, they can have anaphylaxis. It’s still the tick bite; it’s still delayed, and they report a similar frequency of having that sort of 70% of participants have anaphylaxis in their history as well, so they can get it. And it can be quite young too.

Treating and managing alpha-gal syndrome

Dana Parish: It’s really scary. Can you ever, if you know you have alpha-gal and I want to talk about all the different foods and medications and things that people should be aware of if they have alpha-gal, can you pre-medicate, if you’re kind of like, ‘I’m going to a restaurant, it’s my birthday. I don’t know if there’ll be some cross-contamination.’ Can you take Benadryl? Do you always carry an EpiPen? What do you do?

Dana Parish: It’s really scary. Can you ever, if you know you have alpha-gal and I want to talk about all the different foods and medications and things that people should be aware of if they have alpha-gal, can you pre-medicate, if you’re kind of like, ‘I’m going to a restaurant, it’s my birthday. I don’t know if there’ll be some cross-contamination.’ Can you take Benadryl? Do you always carry an EpiPen? What do you do?

Scott Commins: Definitely, we encourage people to have an epinephrine autoinjector, usually in a known spot, whether that’s with them. The alpha-gal allergy sort of changes that a little bit because the reactions don’t usually happen at the restaurant, so to speak. But typically, we are giving folks a prescription for an epinephrine autoinjector because of the idea that even though maybe you haven’t had anaphylaxis yet, there’s always a chance that you could. And so the premedication side of this, some people will, as you said, take a Benadryl or maybe even a longer-acting antihistamine that’s non-sedating ahead of a meal out. It doesn’t necessarily give you that ability to order what you’re allergic to, but you’re trying to order the right thing, but you’re guarding against cross-contamination, right? Like I’m saying. So we have patients who do that to try to minimize any symptoms that could occur. There are also gastrointestinal medicines that some of my patients will take ahead to try to help with that sort of similar idea.

Dana Parish: What is that?

Scott Commins: It’s called Gastrocrom. Crom is short for Cromolyn. There’s a version of Cromolyn that seems to help on the GI side of things, so people use that. The other strategy now is the FDA in February approved omalizumab, which is Xolair for a food allergy indication. So, some patients are turning to Xolair. It’s usually a monthly or twice-a-month injection that binds up the allergic antibody response as a way to try to prevent cross-contamination and accidental reactions as well.

Dana Parish: It doesn’t sound like we have anything yet, but it sounds like there’s some hope coming down the pike. Do you think that’s going to be effective at preventing the onset of these acute reactions?

Scott Commins: Yes, I think after several months on Xolair, it does seem as though it helps patients prevent these accidental cross-contamination reactions. And I think the other part of this is trying to perhaps do trials where we look to see, after a tick bite, if we could intervene to try to prevent that allergic response from even developing. Maybe there are ways that we can try to interrupt quite early on, but we also feel like we need to understand who do we try to interrupt and how we can better predict who might be at risk for developing AGS to target that intervention.

Dana Parish: Do people ever avoid these foods for a period of time and then grow out of it? Do they stop having alpha-gal syndrome? Does that ever happen?

Scott Commins: Yes, it does. It can resolve itself. It does appear that the allergy cells that the tick bite initiates can wane over time. So avoidance of future tick bites during the couple of years after someone develops AGS is critical, we think, for the eventual resolution of the allergy.

“Avoidance of future tick bites during the couple of years after someone develops AGS is critical, we think, for the eventual resolution of the allergy.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

Diagnosis, testing, and avoiding triggers

Dana Parish: Interesting. So what are the animal products and the animals that people are most reacting to? When people come to you for their first appointment, and you need to educate them, what are you telling them?

Scott Commins: We talk a lot about the red meat side of it, so to speak, and also countering that advertising campaign that pork was the other white meat. It is a mammal meat, so beef, pork, lamb, venison, and rabbit are really kind of going through and in some ways listing out the mammalian meats and kind of debunking the idea of the red meat, so to speak. But we often take this very individually, so dairy as a product of cows can bother some people, and when that is true, we ask for them to remove dairy from their diet, and it doesn’t bother everyone. So not everyone with the allergy has to remove dairy. We also find that sometimes the fat content is very important, and so occasionally, people will be able to have small amounts of lower-fat dairy but don’t tolerate ice cream. Other people are exposed to gelatin, which is often derived from mammals and can bother them. So, marshmallows or jello itself, gelatin can be used in capsules, and at the moment, manufacturers do not have to label where the gelatin comes from. So it’s a real challenge for patients because you don’t necessarily know if your Tylenol capsule has gelatin that could come from a plant, a fish, or a pig.

Dana Parish: Are there safe drug lists? I’m sure they can always change their formulation, too, and I’ve experienced that myself.

Scott Commins: There’s not a safe list, and mainly because of what you said, that these manufacturers can change the source of the specific, particularly the inactive ingredients, and they never have to change the label one iota, and that’s completely within the current law and regulation. So just saying on the label that there’s gelatin is all that’s required. So I have struggled to keep up with a list in many ways because it’s just so dynamic, and we don’t have the resources to do that. Fortunately, in the past 12 to 18 months, VeganMed has come online—they’re an independent group of pharmacists who are making it their mission to help people obtain vegan medicines. I think that it initially started from an ethical or religious standpoint, but now, alpha-gal syndrome patients really benefit from that knowledge as well.

Dana Parish: What about wearing leather, wearing wool? For the overwhelming majority of people?

Scott Commins: Wool can be an irritant, and so we see people get itchy/rashy from wool that may even be enhanced in the AGS group. And I do have some patients who report issues with leather, but I would say it’s less than uncommon. It’s rare.

Dana Parish: That’s good to know. I read a fascinating piece. I’m a hundred percent sure you must have read it too in The Atlantic, and I know also you’ve been quoted in The Atlantic before about livestock, about farmers having to sell their flocks, not being able to milk their cows or deliver calves anymore because the amniotic fluid is aerosolizing and they’re having reactions to that. Was this surprising to you? Do you hear from some of these people?

Scott Commins: Yes, I’ve heard from them. It was not surprising to me when Sarah Zang, who wrote that article, reached out because it’s something that we’ve heard from time to time, and so this is exactly why I think it is best called alpha-gal syndrome because it affects beyond just food intake. These are people’s livelihoods, their hobbies, and their passions, and they have to completely reinvent that. And the farmers—I have multiple farmers who’ve had to change what is on their farm or even sell it. We have chefs and restaurateurs who can no longer safely taste the food that they’re making, so they don’t feel comfortable making it. They have to change their line of work as well. So no, it is sad when it happens, but I’m unfortunately well aware of it.

Dana Parish: I also wondered, does this ever extend to people’s household pets?

Scott Commins: Yeah, it is possible. Fortunately, when we see it often, it is more of the: ‘When my dog or cat licks me, I get an itchy spot on my skin where that contact was,’ I’ll occasionally have people say, and these are often—keep in mind—people who have multiple cats or dogs in their home and have a very high dander burden and they may say that they feel as though they’re congested or have some sinus issues in a way that they didn’t before they developed alpha-gal syndrome. But in my experience, it has not been: ‘I now have anaphylaxis upon exposure to my pet.’ I don’t know that I’ve ever seen that.

Dana Parish: When I was growing up, all of us kids that had any kind of allergic stuff would go to the allergist and get shots every week. I don’t think they helped. I was allergic to cats. And dust and the usual stuff you hear about. It sounds like a monoclonal antibody coming down the pike that could be extremely helpful, and that’s wonderful. Is there anything now like that, though, like an allergy shot that people can get to calm this down a little bit?

Scott Commins: The short answer is no. We tried using cat allergy shots, thinking that as a mammal, maybe, and cat is a punchy allergen too, so we were thinking maybe that would help desensitize people, but it didn’t seem to work. I think probably there’s not enough alpha-gal in these cat or dog extracts to modulate that, but one of our goals is to create an allergy shot basically for the tick factors, the tick saliva, and the idea there would be to model what we do for people that may be allergic to bees or wasps where we can’t prevent that initial allergic reaction to the sting, but then we can put you on venom allergy shots and try to prevent any future stings from creating that same allergic risk. And so what we’re trying to do is copy that on the tick side with the idea that, look, we think this thing can go away. The biggest impediment to that is additional tick bites. If we can put you on a tick allergy shot that renders those future bites less immunogenic, meaning they don’t reinvigorate that allergic response, then hopefully this whole thing could go away for people at a three- to five-year time horizon, and maybe we’ve now protected them against future tick bites causing it again. So it’s a definite goal. We’re starting basically in the cell model, in an animal model, because we don’t want to expose folks to tick saliva until we know that it’s safe.

Dana Parish: I’m just curious, we mentioned cats, why are so many people allergic to cats? What is it that makes it punchy?

Scott Commins: The cat allergen is uniquely strong just in the allergen world and carries properties that make it incredibly efficient at activating the allergic response. And this, if you have people or friends or family who are allergic to cats, if they walk into a new environment, they may not even have to see the cat, but they’ll know there’s a cat here and is rarely that dog allergy is rarely that strong.

Dana Parish: I slept at my best friend’s apartment in LA 10 years after she had a cat, and I slept in a spare bedroom where probably the cat spent a lot of her time, and I had a severe allergic reaction 10 years later from whatever was still. And it’s a very specific kind of reaction. It’s like what you said, you walk into the room, my eyes all of a sudden get glassy and itchy and red and I start getting itchy Before I know it, my face is swelling. It’s pretty intense. And my dad has the same thing. Why do we have this intense allergy? So many people I know have it.

Scott Commins: It has more to do with the cat allergen properties than you or your father or others. It’s the cat allergen itself. It is because it’s so unique.

Mental health and support for alpha-gal syndrome

Dana Parish: So you mentioned this earlier, and I know you did an incredible talk on this last week because I’ve heard many people tell me about it. If we could close by talking about the post-traumatic stress element of having this, I’m allergic to Bactrim, and I remember, and it was what you said, I had it many times for UTIs throughout my life, even when I was really kind of young and which turned out to be Lyme, but that’s a whole other story. But Bactrim would help for a period, and then it would come back, and I had this thing my whole life, and one day I took a Bactrim and my mouth swelled up and my eye swelled shut, and I called my pharmacist. I was in my early twenties, and I said, Hey, I’m not sure what’s going on.

And he’s like, where are you? I told him where I was. He goes, ‘Oh, you’re right near NYU. Tell them I sent you, go to the emergency room right now at this very second, and let them know I told you to go.’ So I did have a pretty terrible reaction. So after that, I was really afraid that that was going to happen again. I did feel like I might have died if he hadn’t told me to go. I felt like my life was actually in danger from that response. For years, I did have an allergist at that time who told me, ‘You’re going to have to carry an EpiPen for the rest of your life because allergies are wily, they’re unpredictable, and we don’t know if you’re going to have this again now to something else.’ Honestly, it was terrifying, and I can’t imagine having alpha-gal and having this constant fear hanging over me about food. It’s scary. Do you have a lot of patients who tell you, ‘I’m really traumatized by this’?

Scott Commins: I do, and I’m glad you brought that up. I think it’s probably one of the most important points in all of this, the mental health aspect, the post-traumatic aspect, as you mentioned, it’s probably apart from the diagnosis and being uncertain perhaps about what they should avoid and how deep to go on the food allergy side, the mental health part of having these allergic reactions, and I think particularly the delayed aspect where just because you ate dinner out and you left the restaurant doesn’t mean you successfully avoided. It comes up a lot, and I put myself in this space, too. We don’t talk about it enough as allergists. We need more specifically trained mental health practitioners to help us on this food allergy side. And I think we have known this about food allergy in terms of the anxiety and panic part of that and the PTSD part of that for kiddos for years.

“When you look at study after study in the food allergy space, the things that come up are panic and anxiety around the (allergic) reactions and the exposures to food and not knowing whether something is safe or not.”

– Scott Commins, MD, PhD

I feel like we explore this with our kids and try to reassure them that having some anxiety around what you eat is a natural part of having a food allergy and that we can deal with it. Even studies show that for people who are treated for mental health diagnoses, if they have food allergies, their mental health is better around this because it’s being addressed. By not addressing it, we’re leaving patients in a spot where they don’t have help. And now with AGS, we have these adult patients with a new onset food allergy, and I think they’re not getting the mental health care that they need. So when you look at study after study in the food allergy space, the things that come up are panic and anxiety around the reactions and the exposures to food and not knowing whether something is safe or not.

You’ll have patients who will say, ‘Look, the social aspect of eating has changed for me. So much of what we do in the US, and Europe for that matter, revolves around eating and the socialization of that. For me, a meal is a risk, and it is hard to relax in that space.’ I think we have to talk about it and give resources to our patients to be able to have that aspect addressed.

Resources and future developments for alpha-gal syndrome

Dana Parish: So, are there resources currently? Are there online alpha-gal support groups or people who meet and get together?

Scott Commins: There are support groups online through various social media aspects and avenues, but to my knowledge, there’s not a real formal kind of mental health diagnosis around food allergy. It feels to me like we probably should have that because you can imagine if you’ve had anaphylaxis after eating something when the next reaction develops, you don’t know if the itchy palms and the hives and the GI upset are leading you back to an anaphylactic reaction or if maybe it’s just going to stop at that.

Dana Parish: Do people always have to seek care? I understand you’re saying you need to carry an EpiPen and stuff. Is that the treatment, or do you go, ‘Oh gosh, here it comes. I have to go to urgent care, I have to go over to the ER’?

Scott Commins: Well, epinephrine is the treatment for anaphylaxis, and seeking care in the setting of an allergic reaction is certainly reasonable and probably merits an individual kind of discussion and depends on a lot of different factors, but certainly we want people to think about epinephrine as really the treatment that should be prescribed and undertaken for anaphylaxis.

Dana Parish: Do you need one shot normally? I’m asking because I have a friend who required one for a different anaphylactic reaction but had multiple shots of epinephrine. Is that common?

Scott Commins: Fortunately, it’s not common. It does happen. We have patients who will come to us after having been in the ICU and placed on an epinephrine drip. There are these severe cases. Fortunately, they’re uncommon, if not rare. In the overwhelming majority of instances, a single dose of epinephrine is sufficient to settle the allergic reaction.

Dana Parish: That’s great. I am not sure if I directly asked you this. Does the premedication taking Claritin or Cromolyn as you said before eating your birthday dinner (or whatever) mitigate the risk of a later flare?

Scott Commins: Well, there’s no clinical trial data around that. I think anecdotally what I hear from patients is that they probably feel as though if they’ve done that, that has helped. But it’s hard to say because they’re still practicing an avoidance diet. I think it’s just that little added layer of security.

Dana Parish: It makes sense. I mean, intuitively, it makes sense. Any parting words? Anything important that I didn’t ask you that you want to talk about before we go? And of course, I want to know where people can find you and more information about you and your work.

Scott Commins: I think we’ve covered a lot. One of the things that has come up frequently of late is the idea that people get a tick bite and have a tick panel of blood work done. And I just want to say from the allergy standpoint, that’s not how we envision allergy testing being used. The reason for that is that there’s a high false positive rate with allergy blood tests in general. The alpha-gal test is not immune to that. When we look at the case-control study that I mentioned with the CDC, which was performed both in the UNC allergy clinic and enrolled controls from a rural county just south of the university, 30% of our controls, —and keep in mind to be a control, you had to answer that you both consumed red meat and had no reactions that you could attribute to red meat over years. We asked specifically about nighttime things, and we vetted these controls because we wanted truly negative people—and 30% of them tested positive by blood test for alpha-gal allergy. So we know that in a rural setting, in the Lone Star tick territory, there is a high false positive rate probably just because people are getting tick bites. So we don’t want people starting this avoidance diet just because they’ve had a positive blood test. You want symptoms to drive the testing. So I think that’s an important point. I don’t want people just requesting a test because they’ve had a tick bite. There’s a high chance you could be thrust into this allergy avoidance world given an epinephrine prescription when you may just be a false positive.

Dana Parish: That is great information to have. What is the best way to get diagnosed? I guess that is the question.

Scott Commins: We like symptoms or concern for symptoms to drive the testing, meaning people might notice that they’ve had an episode of hives in the middle of the night or some unexplained gastrointestinal distress, maybe some itching of their palms, right? Maybe they had a tick bite like you mentioned earlier, where it was really slow to heal and it was itchy for a long time, and now I’ve got these new symptoms that maybe I can’t trace specifically to a food, but something feels like it’s changed recently in those scenarios. I think it’s a great use of the alpha-gal blood test to try to understand like, ‘Oh, could this be what has happened?’ as opposed to ‘I had a tick bite, and now I want to get tested for a panel of stuff.’ We don’t like the allergy food tests used in that same way. You wouldn’t test a group of third graders for peanut milk, egg, or tree nut unless they were having symptoms consuming those. So it’s just a weird nuance in the allergy field with our blood tests.

Dana Parish: I think that’s an extremely important point because I can understand the concern, especially parents worrying about their kids. Maybe their kids are a little bit allergic to begin with, and there’s a concern and a fear about it. So we shouldn’t assume that everybody who has that test is going to react.

Scott Commins: Absolutely.

Dana Parish: So what about what you have on your horizon and where we can find you? You have some great talks and Q&As on YouTube, so people should search for your name and find those. But what else can we find out about you?

Scott Commins: We’re trying to curate some of the talks and presentations, and I think for me, the next step in this is to solidify some of that into a website. And then, equally, we’re hoping to establish and launch a podcast to help provide information awareness and education for not only the general public but hopefully for practitioners and providers as well. So, I hope to have both the website and the podcast available within the next several months.

Dana Parish: That’s fabulous. Well, will you let me know when you do so I can share it with the Lyme community and get other doctors to share it because there’s such great interest in your work? Thank you so, so much for your time. You’re so generous, and you’re such a great communicator.

Scott Commins: Well, my pleasure. Thank you so much for the opportunity, and I really enjoyed chatting with you.

Dana Parish: Thank you for joining us for this episode of Ticktective, a program of the Bay Area Lyme Foundation. For more information or to get involved, please visit us at bayarealyme.org.

Biography: Scott P. Commins, MD, PhD, is the William J. Yount Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Associate Chief for Allergy & Immunology Medical Director, University of North Carolina Allergy & Immunology Clinic at Eastowne. His areas of Interest include alpha-gal syndrome (“red meat allergy”), food allergy, anaphylaxis, stinging insect venom allergy, and tick-borne illnesses. Dr. Commins sees patients in the UNC allergy clinic and maintains an active research laboratory. His primary research and clinical interest is alpha-gal syndrome. This unique food allergy appears to be brought on by tick bites and can develop at any time throughout life, even after many years of enjoying beef, pork, or lamb. Patients develop an allergic response to the sugar alpha-gal, and the resulting allergic reactions are often delayed 3–6 hours after eating mammalian meat. Dr. Commins often sees patients in the allergy clinic with difficult-to-diagnose food allergies or allergic reactions. In the research laboratory, the primary question being investigated is the role of the skin and resident cells, including mast cells and basophils, in allergic immune responses. Listen or watch now to help your healing journey. Click here to watch or listen. This blog is part of our BAL Ticktective Transcripts series. If you require a copy of this article in a bigger typeface and/or double-spaced layout, contact us here. Bay Area Lyme Foundation provides reliable, fact-based information about Lyme and tick-borne diseases so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. For more information about Bay Area Lyme, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.